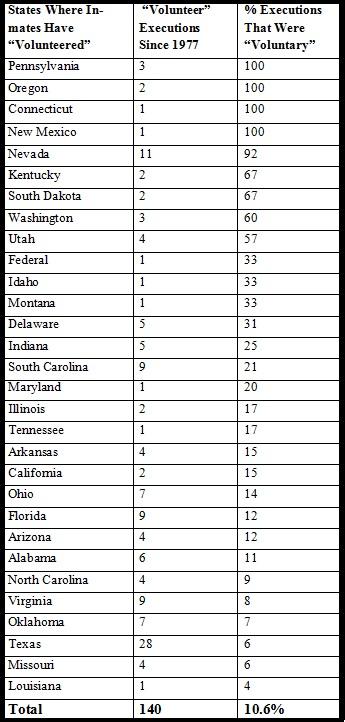

When Robert Gleason Jr. was put to death in Virginia on January 16 (he chose the electric chair) he became the 140th so-called “volunteer” for execution since the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. In fact, over 10% of US executions have been “voluntary,” usually meaning that the prisoner has given up his appeals.

When Robert Gleason Jr. was put to death in Virginia on January 16 (he chose the electric chair) he became the 140th so-called “volunteer” for execution since the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. In fact, over 10% of US executions have been “voluntary,” usually meaning that the prisoner has given up his appeals.

But in Gleason’s case it was more than that. He specifically killed to get the death penalty. He strangled his cellmate and vowed to keep on killing unless he was executed. And this is not the first time someone has committed murder in order to get the state to kill him. In Ohio in 2009, Christopher Newton was put to death for killing his cellmate. He had refused to cooperate with investigators unless they sought the death penalty.

In cases like this, it can be definitively stated that the death penalty did not deter, but in fact incited murder. (Which begs the question for states considering limiting the death penalty to those who kill police or correctional officers: could this actually put them at more risk?)

Most execution “volunteers” give up their appeals out of remorse, or due to mental illness, or with suicidal intent, or some combination of all three. These cases compound the death penalty’s arbitrariness. Capital punishment is supposed to be reserved for the “worst of the worst,” but remorseful, suicidal or mentally ill prisoners aren’t really the “worst,” just the easiest to kill.

It was this arbitrariness that led Oregon’s Governor recently to declare a moratorium on executions, calling it a “perversion of justice” that: “The only factor that determines whether someone sentenced to death in Oregon is actually executed is that they volunteer.” (100% of Oregon executions – 2 out of 2 – have been of “volunteers.”)

The Supreme Court’s 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision, which re-started executions after about a ten year hiatus, envisioned a narrow and rationally applied death penalty that would deter the most heinous crimes committed by the worst offenders. But instead, this “modern” death penalty sometimes incites murder and takes the lives of those who are decidedly not the “worst.” The Court’s vision of a fair and limited death penalty has been overwhelmed by inconveniently complex realities and by the infinitely surprising and bizarre ways human beings actually behave.

In short, it hasn’t worked. And it never will.