Daniel Cook, abused since infancy and now facing execution on August 8 in Arizona, is just the most current example of someone who endured severe childhood abuse only to later face execution. (Cook has a clemency hearing on Aug. 3; the prosecutor opposes his execution and it can still be stopped.)

There have been plenty of others.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In its 1976 Gregg v. Georgia decision, the US Supreme Court allowed executions to resume but required that juries be guided to restrict death sentences to the worst crimes committed by the worst offenders (aka “the worst of the worst”). The Court also endorsed laws “permitting the jury to dispense mercy on the basis of factors too intangible to write into a statute.” Defendants with mitigating circumstances (like youth, diminished mental capacity, or a history of childhood abuse) were supposed to receive lesser sentences.

So why do people with severe child abuse in their backgrounds keep ending up on death row? Are they really among the worst?

Here are five recent examples that Amnesty International has documented, in sometimes disturbing detail:

- Samuel Lopez was executed just last month, also in Arizona. According to one doctor, he “lived much of his life as a feral child.” He grew up in an environment of extreme poverty and violence where he was isolated, neglected and beaten, and witnessed his mother being repeatedly beaten as well.

- When Michael Brawner eight he witnessed the rape of his seven-year-old sister by his father, something that went on for the next five years. To keep him quiet, his father beat him so consistently and severely that he regularly missed school to recover from the beatings. By age 14 he was diagnosed with polysubstance dependency and PTSD, and he was later diagnosed with bi-polar disorder. Mississippi executed him last month.

- Richard Smith was physically abused by his father, and his stepfather. The abuse led to him run away from home at the age of 11 or 12. At a juvenile facility where he was sent, he tried to kill himself to avoid being returned home. When he was returned he was beaten severely, handcuffed, and locked in a cupboard every night for two weeks. Thankfully, his sentence was commuted to life without parole by the Governor of Oklahoma in May 2010.

- As a small child, Steven Woods was sexually abused by his father and hospitalized for self-mutilation and suicidal behavior. He was later physically and emotionally abused by his stepfather, and he was using drugs, including LSD, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, codeine and marijuana, by the age of 13. By age 17 he was homeless and working as a prostitute to obtain money for drugs. The state of Texas put him to death in September 2011.

- Stephen West was born in a mental institution. From the time he was born until he left for the army, he was severely physically abused by both his parents. He was beaten, punched, thrown into walls, and subject to other forms of cruelty including public humiliation, degradation, captivity, and isolation. He continues to face possible execution in Tennessee.

All these men committed serious crimes. But, as boys, they also suffered horrific childhood abuse, and their death sentences (and in some cases executions) make a mockery of the notion that we “dispense mercy”, or that we are limiting capital punishment to the worst possible offenders. We are not. (In fact, we can’t even keep innocent people off of death row.)

More often, those who end up on death row are not the worst offenders, but those who experienced the worst childhoods, or had the worst (or non-existent) mental health care, or were saddled with the worst lawyers (see, for example, all five cases listed above).

Recognizing this, three of the Supreme Court Justices who voted for Gregg have since expressed profound regret for that decision.

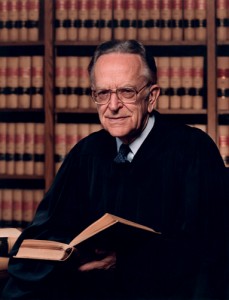

One of them, Justice Harry Blackmun, announced his regret 18 years ago in a powerful dissent, writing: “The basic question–does the system accurately and consistently determine which defendants ‘deserve’ to die?–cannot be answered in the affirmative … The path the Court has chosen lessens us all.”