As Uganda's ruling party, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) looks ahead to the 2016 elections, which will mark President Museven's 30th year in power, new laws have been enacted or proposed with a damaging effect on the human rights of Ugandans.

This report documents the cumulative human rights impact of three pieces of legislation – the Public Order Management Act (POMA), the Anti-Pornography Act (APA), and the now nullified Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA). These Acts were all passed by the Parliament of Uganda and signed into law between August 2013 and February 2014, though the AHA had been debated for over four years before it was passed. This flurry of repressive and discriminatory legislation represents an increasing use of "rule by law" to intensify restrictions on free expression, association and assembly in place since the reintroduction of multiparty politics in 2005.

While these laws have had a repressive and discriminatory impact, the causes of this legislation are manifold. The POMA was first introduced as a bill as President Museveni and the NRM faced more challenges from outside and within the ruling party. The AHA, introduced as a Private Member's bill rather than government legislation, demonstrates the rising influence of religion on law-making. As the debate around it took shape, however, it drew in broader identity issues, such as Uganda's relationship with the Global North, cultural autonomy and family values. These factors also shaped the context in which the APA became law.

Uganda's development partners' response to the AHA was much stronger, in words and actions, than their response to the POMA or the APA. Many Ugandan civil society actors feel that donors have not demonstrated sufficient concern about the rollback of other human rights. The focus on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) rights was counterproductive and ultimately entrenched the misperception that this was an imposition from the Global North.

The Acts collectively reinforce state control and restriction of expression, assembly and association. They have given the authorities enormous discretionary power to enforce their often vaguely defined provisions. After the AHA was passed by Parliament, LGBTI individuals were arbitrary arrested by the police, including when reporting crimes, and some reported being beaten and groped by the police and other detainees in custody. The POMA has led to spates of police suppression of public assemblies, including gatherings involving political opposition groups. It has had a chilling effect on the ability of civil society to organize, even styming attempts to challenge the laws themselves.

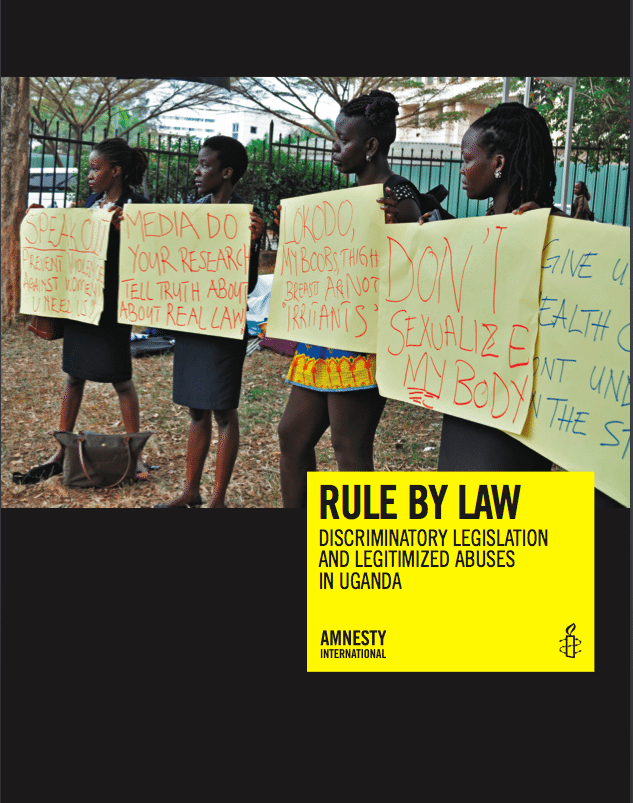

The vitriolic rhetoric from some religious figures and politicians which accompanied the passage of the AHA and the APA into law stoked homophobia and encouraged mob justice targeting women. Immediately after the APA and AHA were signed, women seen to be “dressed indecently” and individuals believed to be LGBTI were attacked in the streets, stripped and beaten. Other LGBTI people were evicted from their homes, lost their jobs, and faced challenges accessing healthcare. The impact was wide-reaching and the ensuing fear pervasive.

The Ugandan government is violating its obligations to protect its citizens against human rights abuses by non-state actors. Discrimination, coupled with a failure by the police and other authorities to respond appropriately to human rights violations and abuses, has fostered a climate where impunity is tolerated and propagated by the state. Broadly worded provisions in the laws have been interpreted by the general public in a way that encourages these abuses. The government’s failure to clarify these laws shows its complicity in the abuses, as well as its failure to ensure equal access to justice and the right to an effective remedy.

The impact of the laws has changed over time. The POMA was invoked more in the first quarter of 2014 to supress public assemblies, but continues to have a chilling effect. The immediate impact of the APA peaked in the days after it was signed, but longer-term it reinforces discrimination against women and gender stereotypes. Similarly, the AHA also had an immediate impact after it was passed by Parliament. Though the Constitutional Court’s nullification of the AHA on procedural grounds has resulted in a reduction in these abuses, by not tackling substantive rights violated by the law, the ruling was a missed opportunity to address homophobia which increased while the law was in force, and which persists as same- sex sexual relations between consenting adults continue to be criminalized under section

Uganda's Penal Code.

Amnesty International calls on the Government of Uganda to uphold its obligations under international human rights law. Specifically, it is asking the Ugandan government to repeal discriminatory legislation, to ensure the government is not complicit in human rights abuses stemming from such legislation, and to protect all Ugandans, including women, LGBTI people and political activists from discrimination, harassment and violence by state and non- state actors.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Government of Uganda:

To the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Uganda Police Force:

To the Ministry of Public Health:

To the World Bank:

To states providing development assistance to Uganda:

To the African Commission: