Through eyewitness testimony and expert analysis of satellite images, Remaking Rakhine State reveals how flattening of Rohingya villages and new construction have intensified since January in areas where hundreds of thousands fled the military’s campaign of ethnic cleansing last year. New roads and structures are being built over burned Rohingya villages and land, making it even less likely for refugees to return to their homes.

“What we are seeing in Rakhine State is a land grab by the military on a dramatic scale. New bases are being erected to house the very same security forces that have committed crimes against humanity against Rohingya,” said Tirana Hassan, Amnesty International’s Crisis Response Director.

“This makes the voluntary, safe and dignified return of Rohingya refugees an even more distant prospect. Not only are their homes gone, but the new construction is entrenching the already dehumanizing discrimination they have faced in Myanmar.”

Bulldozing and destruction

The Myanmar authorities launched a vicious campaign of ethnic cleansing little more than six months ago, on 25 August 2017, in response to attacks by the Rohingya armed group the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA).

The military killed women, men, and children, committed rape and other forms of sexual violence against women and girls and systematically burned hundreds of villages, clearly committing crimes against humanity. More than 670,000 people have fled into Bangladesh.

Although the violence in Rakhine State has subsided, the campaign to drive Rohingya out of their homeland – and ensure they cannot return – continues but has taken on new forms.

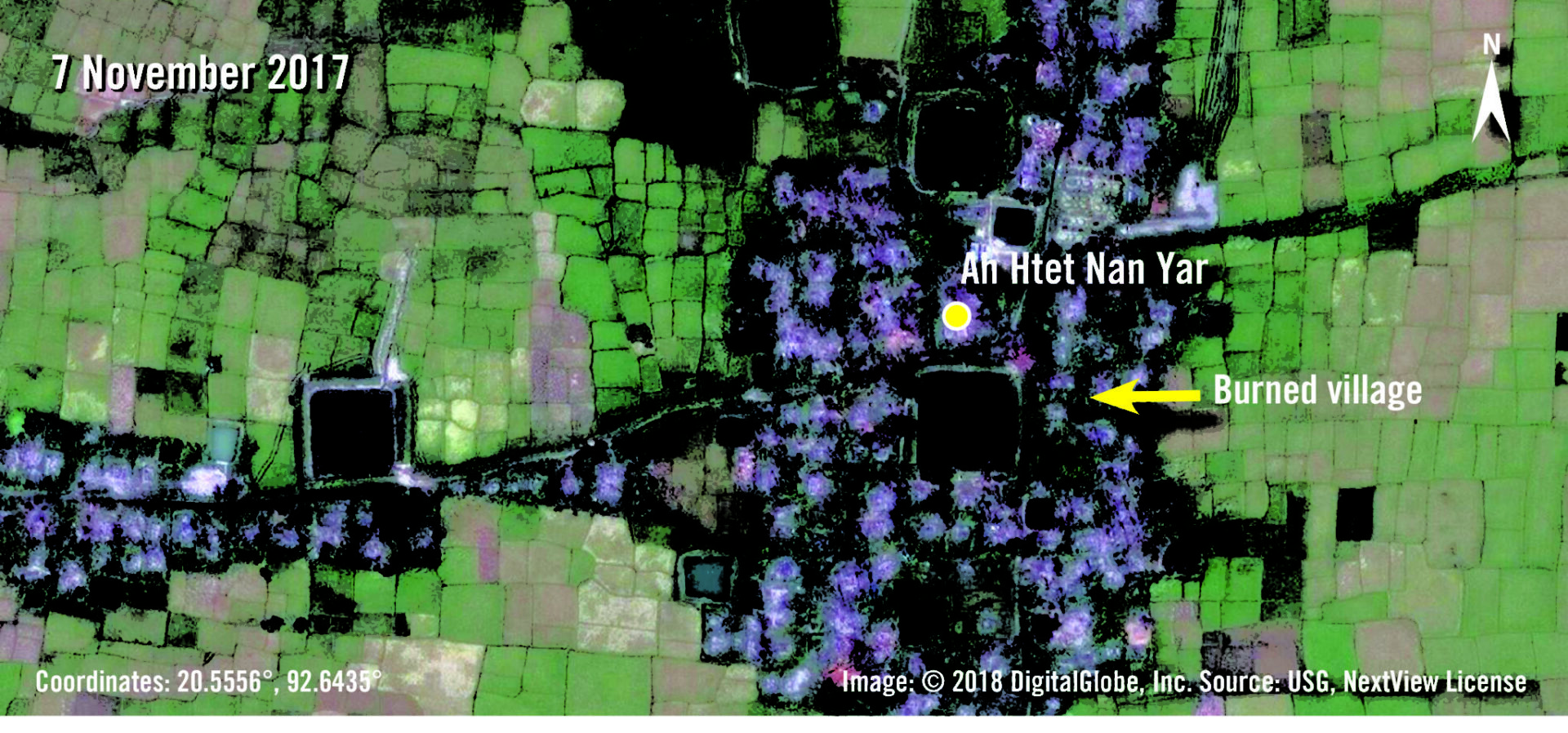

Amnesty International’s latest research reveals how whole villages of burned Rohingya houses have been bulldozed since January. Even surrounding trees and other vegetation have been removed, rendering much of the landscape unrecognizable. This raises serious concerns that the authorities are destroying evidence of crimes against the Rohingya, which could hinder future investigations.

“The bulldozing of entire villages is incredibly worrying. Myanmar’s authorities are erasing evidence of crimes against humanity, making any future attempts to hold those responsible to account extremely difficult,” said Tirana Hassan.

Amnesty International has also documented recent examples of looting, deliberate burning and demolition of abandoned Rohingya homes and mosques across northern Rakhine State.

New infrastructure for security forces

Even more troubling than the destruction is what is being built in its place. Authorities have launched an operation to rapidly expand security infrastructure across Rakhine State, including bases to house the military and Border Guard Police, as well as helipads.

The pace of construction is alarming. Satellite imagery reveals how, in just a few months, new bases have been erected over torched Rohingya land, with whole villages and even nearby forests cleared to make room.

Amnesty International’s analysis of satellite imagery has confirmed that at least three new security bases are being built in northern Rakhine State – two in Maungdaw Township and one in Buthidaung Township. Construction appears to have started in January.

The largest of the new bases is in the village of Ah Lel Chaung in Buthidaung Township, where eyewitnesses said that the military forcibly evicted Rohingya people from certain areas to make way for construction. Many of the villagers saw no option but to flee into Bangladesh.

“People are in a panic. No one wants to stay because they are afraid of more violence against them,” said a 31-year-old man who fled to Bangladesh in January when the military erected a new fence and security post close to his village.

In the once mixed ethnicity village of Inn Din – where Amnesty International has documented how security forces and their proxies killed Rohingya villagers and torched their homes in late August and early September 2017 – satellite imagery shows what appears to be a new security force base being built where the Rohingya part of the village used to be.

Housing and refugee reception centres

Satellite imagery also shows how new refugee reception centres – meant to “welcome” Rohingya who return from Bangladesh – are surrounded by security fences and close to areas with a heavy presence of military and border guard personnel. A massive new transit centre to temporarily house returning Rohingya is built on top of a burned Rohingya village in Maungdaw Township, and also shows signs of heightened security.

There are serious concerns that the Myanmar authorities are planning to house Rohingya in the centres for a prolonged period and restrict their freedom of movement. Tens of thousands of Rohingya, who were driven from their homes during waves of violence in 2012, have for years been confined to open-air prisons in squalid displacement camps. Most rely on aid for their basic needs.

Eyewitnesses also told Amnesty International how non-Rohingya people were living in new villages that have been built on burned Rohingya homes and farmland over the past months. This is worrying since authorities have in the past resettled members of other ethnic groups into Rakhine State as part of efforts to develop the region.

“Rakhine State is one of the poorest parts of Myanmar and investment in development is sorely needed. But such efforts must benefit everyone in the state regardless of their ethnicity, not entrench the existing system of apartheid against Rohingya people,” said Tirana Hassan.

“The remaking of Rakhine State is taking place in a shroud of secrecy. The authorities cannot be allowed to continue their campaign of ethnic cleansing in the name of ‘development’.”

“The international community, and in particular each donor state, has a duty to ensure that any investment or assistance it provides does not contribute to human rights violations. Contributing to entrenching a system that systematically discriminates against Rohingya and that makes the return of refugees even less likely could amount to assisting in crimes against humanity.”