Scores of youths in Iran are languishing on death row for crimes committed under the age of 18, said Amnesty International in a new report published today. The report debunks recent attempts by Iran’s authorities to whitewash their continuing violations of children’s rights and deflect criticism of their appalling record as one of the world’s last executioners of juvenile offenders.

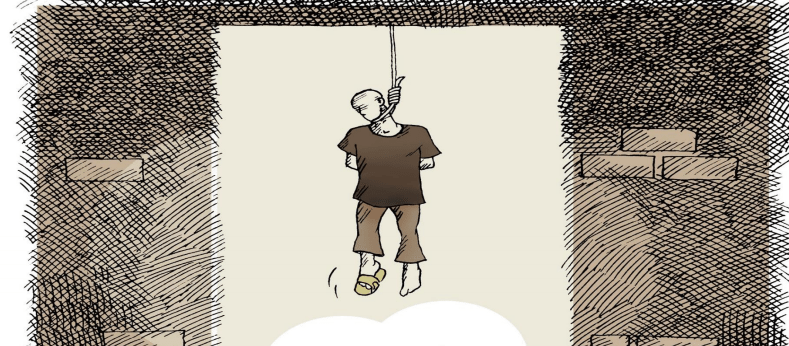

Growing Up on Death Row: The Death Penalty and Juvenile Offenders in Iran reveals that Iran has continued to consign juvenile offenders to the gallows, while trumpeting as major advances, piecemeal reforms that fail to abolish the death penalty against juvenile offenders.

“This report sheds light on Iran’s shameful disregard for the rights of children. Iran is one of the few countries that continues to execute juvenile offenders in blatant violation of the absolute legal prohibition on the use of the death penalty against people under the age of 18 years at the time of the crime,” said Said Boumedouha, deputy director of Amnesty International’s Middle East and North Africa Program.

“Despite some juvenile justice reforms, Iran continues to lag behind the rest of the world, maintaining laws that permit girls as young as nine and boys as young as 15 to be sentenced to death.”

In recent years the Iranian authorities have celebrated changes to the country’s 2013 Islamic Penal Code that allow judges to replace the death penalty with an alternative punishment based on a discretionary assessment of juvenile offenders’ mental growth and maturity at the time of the crime. However, these measures are far from a cause for celebration. In fact, they lay bare Iran’s ongoing failure to respect a pledge that it undertook over two decades ago, when it ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), to abolish the use of death penalty against juvenile offenders completely.

As a state party to the CRC Iran is legally obliged to treat everyone under the age of 18 as a child and ensure that they are never subject to the death penalty nor to life imprisonment without possibility of release.

However, Amnesty International’s report lists 73 executions of juvenile offenders which took place between 2005 and 2015. According to the UN at least 160 juvenile offenders are currently on death row. The true numbers are likely to be much higher as information about the use of the death penalty in Iran is often shrouded in secrecy.

Amnesty International has been able to identify the names and location of 49 juvenile offenders at risk of the death penalty in the report. Many were found to have spent, on average, about seven years on death row. In a few cases documented by Amnesty International, the time that juvenile offenders spent on death row exceeded a decade.

“The report paints a deeply distressing picture of juvenile offenders languishing on death row, robbed of valuable years of their lives – often after being sentenced to death following unfair trials, including those based on forced confessions extracted through torture and other ill-treatment,” said Boumedouha.

In a number of cases the authorities have scheduled the executions of juvenile offenders and then postponed them at the last minute, adding to the severe anguish of being on death row. Such treatment is at the very least cruel, inhuman and degrading.

‘Piecemeal’ reforms failing to deliver justice

Iran’s new Islamic Penal Code adopted in May 2013 had sparked guarded hopes that the situation of juvenile offenders under a death sentence would finally improve, at least in practice. The code allows judges to assess a juvenile offender’s mental maturity at the time of the offence, and potentially, to impose an alternative punishment to the death penalty on the basis of the outcome. In 2014, Iran’s Supreme Court confirmed that all juvenile offenders on death row could apply for retrial.

Yet almost three years after the changes to the Penal Code, the authorities have continued to carry out executions of juvenile offenders, and in some cases, they even often fail to informed the juvenile offenders of their right to apply for a retrial.

Tragically, the report also points to a growing trend where juvenile offenders retried under recent reforms are judged to have attained “mental maturity” at the time of the crime and resentenced to death, in blatant evidence of how little has changed.

“Retrial proceedings and other piecemeal reforms had been hailed as possible steps forward for juvenile justice in Iran but increasingly they are being exposed as whimsical procedures leading to cruel outcomes,” said Boumedouha.

In some cases, judges have concluded that a juvenile offender was “mature” based on a handful of simple questions such as whether he or she understood that it is wrong to kill a human being. They have also repeatedly confused the issue of lack of maturity of children due to their age with the diminished responsibility of individuals with mental illness, concluding that a juvenile offender was not “afflicted with insanity” and therefore deserved the death penalty.

Fatemeh Salbehi was executed in October 2015 for murdering her husband whom she was forced to marry at 16. She was resentenced to death after a retrial session lasting only a few hours in which the psychological assessment was limited to a few basic questions such as whether or not she prayed or studied religious textbooks. In five other cases Hamid Ahmadi, Amir Amrollahi, Siavash Mahmoudi, Sajad Sanjari, and Salar Shadizadi were resentenced to death after courts presiding over their retrials concluded that they understood the nature of the crime and were not insane.

“The persisting flaws in Iran’s treatment of juvenile offenders highlight the continuing and urgent need for laws that categorically prohibit the use of the death penalty against juvenile offenders,” said Boumedouha. “The life or death of a juvenile offender must not be left at the whim of judges. Instead of introducing half-hearted reforms that fall woefully short, Iran’s authorities must accept that what they really need to do is commute the death sentences of all juvenile offenders, and end the use of the death penalty against juvenile offenders in Iran once and for all.”

As Iran re-enters the world of international diplomacy it is also crucial that world leaders use such new channels to raise the cases identified in this report with the Iranian authorities and to urge them to immediately commute all death sentences for juvenile offenders.

In June 2015 Iran introduced reforms specifying that juveniles accused of a crime must be dealt with by specialized juvenile courts. Previously juvenile offenders accused of capital crimes were generally prosecuted by adult courts.

Although the introduction of specialized juvenile courts is a welcome step, it remains to be seen whether this will prevent further use of the death penalty against juvenile offenders in practice.

Over the past decade, interdisciplinary social science studies on the relationship between adolescence and crime, including neuroscientific findings on brain maturity of teenagers, have been cited in support of arguments for considering juveniles less culpable than adults. Such findings were invoked during arguments which ultimately persuaded the US Supreme Court to abolish the death penalty against individuals convicted of committing a crime while under 18 years of age in 2005.