On the eve of an emergency summit in Brussels, Amnesty International is publishing a Blueprint for Action calling on European governments to take immediate and effective steps to end an ongoing catastrophe that has left thousands of refugees and migrants dead.

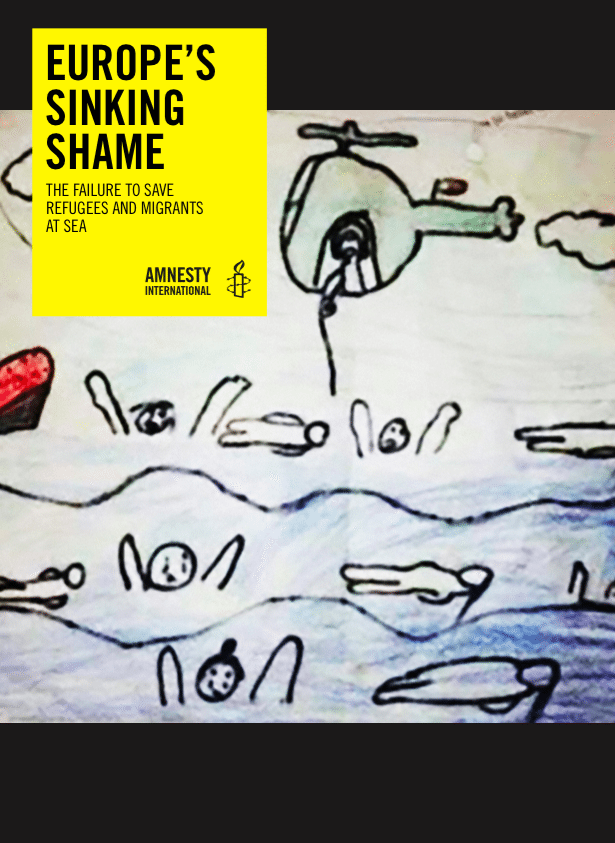

The briefing, Europe’s Sinking Shame: The Failure to Save Refugees and Migrants at Sea, documents testimonies of shipwreck survivors. It details the challenges and limitations of current search and rescue operations in the central Mediterranean and sets out ways in which this can be remedied. It calls for the immediate launch of a humanitarian operation to save lives at sea, with adequate ships, aircraft, and other resources, patrolling where lives are at risk.

On Monday, April 20, in a shift from previous policy, the European Union committed to bolster search and rescue capacity and Member States must now translate this pledge into action.

The briefing shows the decision to end the Italian Navy’s humanitarian operation, Mare Nostrum, at the end of 2014, has contributed to a dramatic increase in migrant and refugee deaths at sea. If figures from the latest incidents are confirmed, as many as 1,700 people will have perished this year, 100 times more than in the same period in 2014.

The myth that Mare Nostrum acted as a “pull-factor” is also dispelled by figures which show that the number of refugees and migrants attempting to cross into Europe by sea has increased since the end of the operation. Indeed 2015 has already seen record numbers of refugees and migrants attempting to cross into Europe by sea, with over 24,000 arriving in Italy.

After Mare Nostrum ended, European governments instructed the EU border agency, Frontex, to set up Operation Triton.

Triton is not a search and rescue operation. Unlike Mare Nostrum’s ships whose area of operation extended south of Lampedusa for about 100 nautical miles (nm), Triton is limited to a border patrol 30nm off the Italian and Maltese coasts, far from where the vast majority of boats get into trouble.

Frontex itself has admitted that its resources are “appropriate to its mandate, which is to control the EU’s borders, not to police 2.5million km2 of the Mediterranean.” Instead search and rescue operations largely fall to coast guard vessels. Admiral Giovanni Pettorino, head of the Italian coast guard's Maritime Rescue Coordination Centres, told Amnesty International that his vessels “won’t be able to take them all, if we remain the only ones to go out there.”

In addition, merchant vessels play a large role in current rescue operations, although they are not designed, equipped or trained for maritime rescue. Despite all actors’ efforts, and having saved of tens of thousands of lives this year, they cannot be expected to address the magnitude of the current humanitarian crisis.

Drowning by numbers

On April 18, 2015 estimates suggest that more than 800 migrants and refugees drowned during an attempted rescue by a merchant ship. Their boat capsized as those on board surged to one side, according to the coast guard. This echoes the testimonies of survivors of other tragedies in Amnesty International’s briefing.

Mohammad, a 25-year-old Palestinian man from Lebanon described how, on March 4, 2015, the boat he was on with 150 people aboard capsized when a large tug boat approached to assist them. "They threw a rope ladder…Many tried to get on it and the boat capsized …I fell into the water…Immirdan, a Syrian woman died with her one-year old son.”

As the shipping industry has recognized, large scale rescues by merchant vessels carry many more risks underlining the need for a professional humanitarian operation.

On March 31, 2015, the representatives of the main European and global shipping industry associations and seafarers’ unions described the current situation as “untenable” and called on states to increase resources and support for search and rescue operations. In a joint statement they said “…it is unacceptable that the international community is increasingly relying on merchant ships and seafarers to undertake more and more large-scale rescues.”

On February 8, 2015 following a distress call, Italian coast guards braved high seas and freezing temperatures to rescue 105 people from an overcrowded dinghy. Their boat was part of a group of four that had set off from Libya the day before and got into trouble. A total of more than 330 refugees and migrants died on that day. Apart from two commercial vessels in the area, only the Italian coast guard was available to provide assistance.

But facilities on the two uncovered patrol boats were insufficient to provide warmth and shelter to the rescued and 29 of them died of hypothermia on board. Salvatore Caputo, a nurse on board one of the coast guard vessels, told Amnesty International: “To keep them warm we made them rotate inside the cabin, but it was all very difficult…I felt so enraged: saving them and then seeing them die like that.”

Ready to act

Massimiliano Lauretti, a captain in the Italian navy, told Amnesty International that a humanitarian operation could be organized within days if an order to do so was received.

“The Italian Navy stands ready. We have well-rehearsed procedures. We have built our experience. If we are asked, we can re-start a humanitarian operation in a very short time, 48-72 hours, give or take.”

Amnesty International is calling on all European heads of state and government attending tomorrow’s summit to immediately establish an effective operation to save lives at sea. They must authorize the immediate deployment of sufficient naval and aerial resources along the main migration routes to rescue people. Until this is in place European governments should urgently provide Italy and Malta with financial and logistical support enabling them to step up their search and rescue capacity.