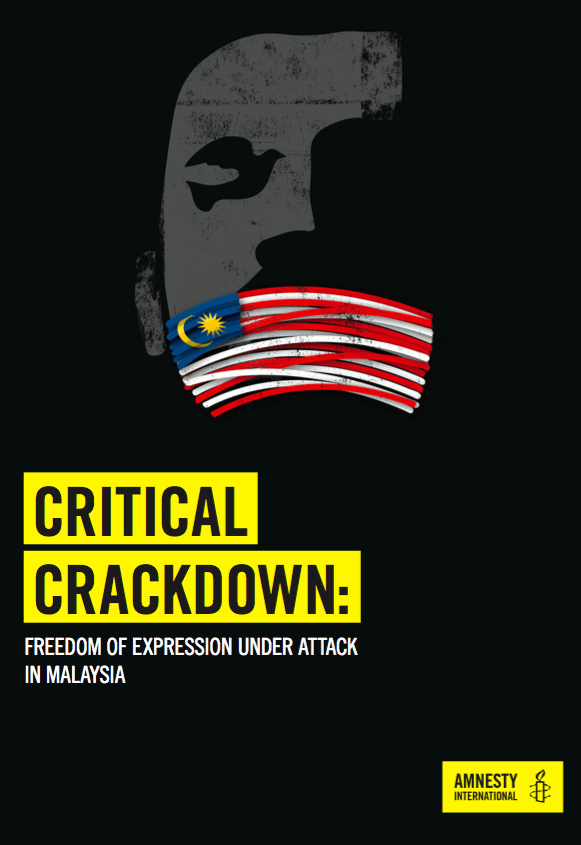

Malaysia’s government has launched an unprecedented crackdown through the Sedition Act over the past two years to silence, harass and lock up hundreds of critics, Amnesty International said in a new briefing today.

Critical Repression: Freedom of Expression Under Attack in Malaysia shows how the use of the Sedition Act – which gives authorities sweeping powers to target those who oppose them – has skyrocketed since the Barisan Nasional coalition government narrowly won the 2013 general elections, with around 170 sedition cases in that period.

In 2015 alone, at least 91 individuals were arrested, charged or investigated for sedition – almost five times as many as during the law’s first 50 years of existence.

“Speaking out in Malaysia is becoming increasingly dangerous. The government has responded to challenges to its authority in the worst possible way, by tightening repression and targeting scores of perceived critics,” said Josef Benedict, Amnesty International’s South East Asia Deputy Campaigns Director.

“The Sedition Act has no place in a modern, rights-respecting society – it is a severely repressive law that has become the authorities’ weapon of choice when lashing out at any opposition.

“The numbers speak for themselves – the staggering rise in sedition cases over the past years highlight the rapidly shrinking space for freedom of expression.”

Malaysian authorities have cast a wide net of repression in their use of the Sedition Act, targeting a range of individuals including rights activists, journalists, lawyers and opposition politicians.

The briefing is released ahead of the trial hearing on January 28 of the cartoonist Zunar, who could face a long period in prison on sedition charges relating to a series of tweets he made which were critical of the government.

Another recent casualty of the act, student activist Khalid Ismath, had three sedition charges levelled against him in October 2015 simply for a Facebook post denouncing the Malaysian police for abuse of power. Ismath is currently awaiting trial.

The threat of arrest has had a chilling effect on public debate and freedom of expression in Malaysia, not least for independent media. Susan Loone, a journalist arrested on sedition charges in 2014 for an article criticizing the police, told Amnesty International that her colleagues sometimes self-censor to avoid harassment by authorities.

But Loone herself remains defiant: “If writing the truth, asking questions, taking a minister to task or making a powerful figure accountable are seditious, then let us all be seditious.”

The Sedition Act is a colonial-era relic, first introduced during British rule of Malaysia in 1948 to combat the independence movement. Those found guilty can face three years in prison, be fined up to 5,000 Malaysian Ringgit (USD1,300) – or both – for their first offence. Those convicted for a subsequent offence can face up to five years in jail.

In 2012, Prime Minister Najib Razak vowed to repeal the law, but the government has not only reneged on that promise but actually strengthened and widened the scope of the Sedition Act.

An amendment to the act rushed through parliament in April 2015 after less than a day’s debate added criticism of religion to the list of sedition offences; reduced the discretion of judges in sentencing, requiring them to impose prison sentences of between three and seven years; and also brought electronic media and sharing on social media under the act.

“It is deeply worrying that Malaysia’s authorities are moving to make the Sedition Act an even more potent tool for repression, rather than repealing it as they have promised,” said Benedict. “The Internet and social media have become invaluable to many activists around Malaysia, something the authorities are moving swiftly to repress.”

Amnesty International calls on the Malaysian authorities to urgently repeal the Sedition Act, and to quash the convictions against any individuals sentenced under the act simply for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression and ensure that they are immediately and unconditionally released.

The organization also urges Malaysia to review and amend all other laws which restrict the right to freedom of expression, and bring them into strict compliance with international human rights law and standards.