Burundian authorities repressed demonstrations as if they were an insurrection, and now the country appears to be on the verge of conflict, Amnesty International warned in a new report, Braving Bullets – Excessive force in policing demonstrations in Burundi, released today.

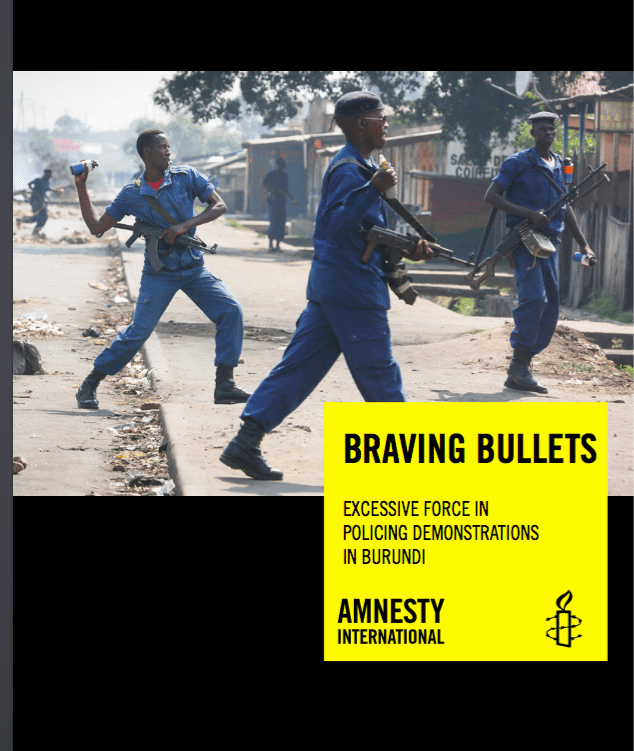

Amnesty International’s investigation in May and June 2015 found that Burundian police used excessive lethal force, including against women and children, to silence those opposed to President Pierre Nkurunziza’s bid for a third-term.

“It is a tragedy that demonstrators had to brave bullets to try to have their voices heard,” said Sarah Jackson, Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for East Africa, the Horn and the Great Lakes.

“The Burundian authorities must urgently, thoroughly and transparently investigate the use of excessive lethal force against largely peaceful demonstrators and bring to justice anyone found to be responsible. This is absolutely important to restore confidence in security services and reduce the risk of people finding more violent ways to express political grievances.”

As of June 29, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), at least 58 people, including two policemen, two military and one member of the ruling party’s youth wing, the Imbonerakure, have been killed since demonstrations erupted on April 26, 2015.

The police shot unarmed demonstrators running away from them. Even when children were present during demonstrations police still failed to act with restraint using live ammunition and tear gas.

Though most protesters remained peaceful, some used violence in response to excessive force by the police. Amnesty International documented how protesters threw stones injuring policemen, beat up a policewoman, vandalized property, and killed one Imbonerakure member.

Treating largely peaceful demonstrators and entire residential areas as if they were part of an insurrection was counter-productive and escalated protests rather than defusing them.

The violations by police against protesters – as well as government statements before the demonstrations pre-emptively characterizing them as an insurrection – show that the Burundian authorities sought not just to disperse demonstrations, but to punish protesters for expressing their political views.

The assault on protesters was coupled with a crackdown on media. From the first day of the protests, authorities prevented radio stations from broadcasting outside of Bujumbura. On May 13, after military officers staged an attempted coup, the police physically attacked independent media facilities, and they have since been unable to broadcast.

Justice denied

“Despite dozens of protesters killed, and a myriad more injured by police, the Burundian authorities have failed to investigate,” said Sarah Jackson.

“The government must suspend suspects pending criminal investigations and prosecutions to end this pattern of police brutality and impunity.”

Contrary to the report’s findings, a presidential advisor told Amnesty International that some of the incidents were committed by people wearing police uniforms, but not the police themselves. According to the Deputy Police Spokesperson, five policemen are under investigation in relation to the demonstrations.

No victims or family members interviewed by Amnesty International had filed complaints with the police citing fear of reprisals following intimidation by police or intelligence agents.

A divided police force

On July 8, the Police Spokesman who has now fled the country, gave a media interview where he said a “parallel police” had emerged and that “some policemen have been assassinated” because they had different opinions.

The report includes accounts of policemen increasingly frustrated with orders they received, which contradicted their training in human rights. Some police flatly refused to follow orders.

Testimonies of brutality

A witness to protests on May 4 near Ntahangwa Bridge in Bujumbura told Amnesty International:

“They (the police) shot at people who were demonstrating peacefully. It was unbelievable. People were fleeing in the river, the police shot at people running away in the river.”

A local journalist told Amnesty International:

“Once in Nyakabiga, I saw an officer taking away the weapon of another policeman after he had killed a young man. He told him ‘you have not received the order to shoot people’. I have also seen policemen stopping their colleagues from shooting live ammunition at demonstrators or using tear gas […] But then three pick-ups arrive, drop some policemen who just start shooting before leaving again. I saw this in Nyakabiga, Musaga and Cibitoke on several occasions. […] I heard several times policemen saying about demonstrators ‘let’s kill them’ and some others saying no. Once in Musaga, I saw a policeman crying, who said ‘I am tired of this, when will it stop?’”