On April 21, Reuters reported that Facebook has begun to significantly step up its censorship of “anti-state” posts in the country. This follows pressure from the authorities, including what the company suspects were deliberate restrictions placed on its local servers by state-owned telecommunications companies that caused Facebook to become unusable for periods of time.

“The revelation that Facebook is caving to Viet Nam’s far-reaching demands for censorship is a devastating turning point for freedom of expression in Viet Nam and beyond,” said William Nee, Human Rights Advisor at Amnesty International.

“The Vietnamese authorities’ ruthless suppression of freedom of expression is nothing new, but Facebook’s shift in policy makes them complicit.”

“Facebook must base its content regulation on international human rights standards for freedom of expression, not on the arbitrary whims of a rights-abusing government. Facebook has a responsibility to respect freedom of expression by refusing to cooperate with these indefensible takedown requests.”

The Vietnamese authorities have a long track record of characterizing legitimate criticism as “anti-state” and prosecuting human rights defenders for “conducting propaganda against the state.” The authorities have been actively suppressing online speech amid the COVID-19 pandemic and escalating repressive tactics in recent weeks.

“It is shocking that the Vietnamese authorities are further restricting its peoples’ access to information in the midst of a pandemic. The Vietnamese authorities are notorious for harassing peaceful critics and whistleblowers. This move will keep the world even more in the dark about what is really happening in Viet Nam,” said William Nee.

Facebook succumbs to Viet Nam pressure

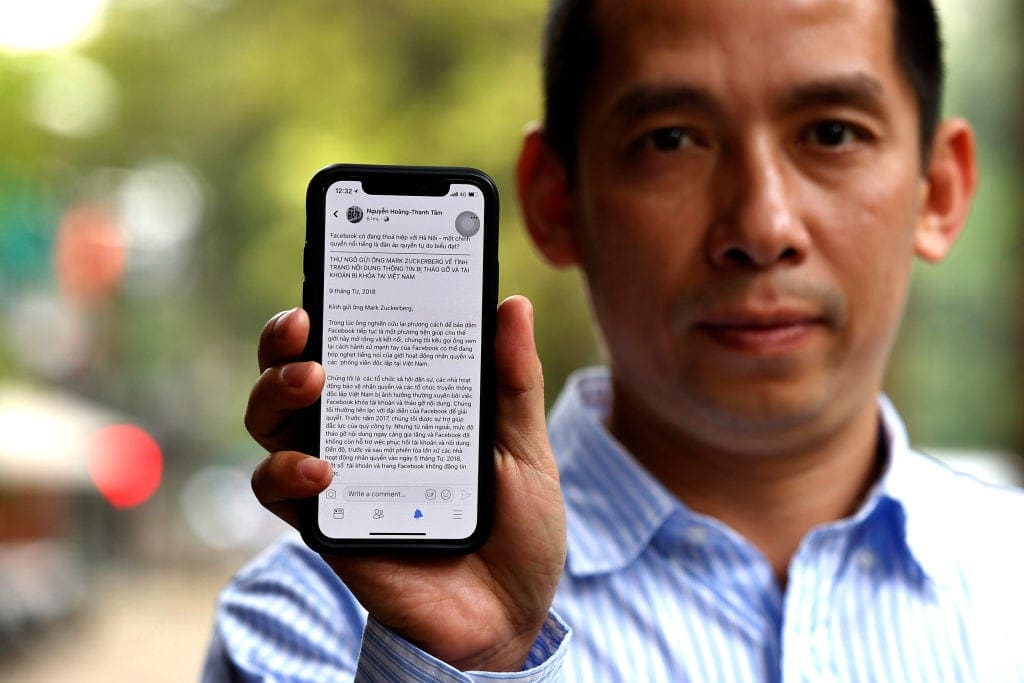

Facebook’s decision follows years of efforts by Vietnamese authorities to profoundly undermine freedom of expression online, during which they prosecuted an increasing number of peaceful government critics for their online activity and introduced a repressive cybersecurity law that requires technology companies to hand over potentially vast amounts of data, including personal information, and to censor users’ posts.

“Facebook’s compliance with these demands sets a dangerous precedent. Governments around the world will see this as an open invitation to enlist Facebook in the service of state censorship. It does all tech firms a terrible disservice by making them vulnerable to the same type of pressure and harassment from repressive governments,” said William Nee.

“While it is true that social media has positively transformed the landscape for freedom of expression in Viet Nam, this is only because Vietnamese internet users have used these platforms to express critical views and uncover human rights abuses. It is the fundamental right to freedom of expression – not profit and ‘market access’ – that must be protected at all costs,” said William Nee.

In a report published last year, Amnesty International found that around 10% of Viet Nam’s prisoners of conscience – individuals jailed solely for peacefully exercising their human rights – were jailed in relation to their Facebook activity.

Recent surge in censorship and intimidation

In January 2020, the Vietnamese authorities launched an unprecedented crackdown on social media, including Facebook and YouTube, in an attempt to silence public discussion of a high-profile land dispute in the village of Dong Tam, which has attracted persistent allegations of corruption and led to deadly clashes between security forces and villagers.

The crackdown has only intensified since the onset of COVID-19. Between January and mid-March, a total of 654 people were summoned to police stations across Viet Nam to attend “working sessions” with police related to their Facebook posts connected to the virus, among whom 146 were subjected to financial fines and the rest were forced to delete their posts.

On April 15, authorities introduced a sweeping new decree, 15/2020, which imposes new penalties on alleged social media content which falls foul of vague and arbitrary restrictions. The decree further empowers the government to force tech companies to comply with arbitrary censorship and surveillance measures.

On April 18, authorities in Hau Giang province arrested Dinh Thi Thu Thuy, 38, for “conducting propaganda against the state” under Article 117 of the 2015 Penal Code. Police accuse Dinh Thi Thuy Thuy of “posting and sharing hundreds of anti-state contents on Facebook.” This charge carries a prison sentence of up to twenty years.

Separately, on April 12, police in Can Tho city arrested and detained Ma Phung Ngoc Tu, 28, for “abusing democratic freedom” under Article 331 of the 2015 Penal Code. Police accuse Ma Phung Ngoc Tu of “posting and sharing 14 posts about coronavirus and bad-mouthing the regime”. The charge carries a prison sentence of up to seven years. He remains in pre-trial detention.

On April 10, the authorities in Lam Dong province summoned Dinh Vinh Son, 27, for spreading “fake news” about COVID-19, making him the first person in Viet Nam to be charged for circulating information about the pandemic. He was charged under Article 288 of the 2015 Penal Code for “Illegal provision or use of information on computer networks or telecommunications networks”. The charge carries a prison sentence of up to seven years.