African and global human rights bodies must urgently investigate killings of civilians by the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF) in Merawi town, Amhara region, after fighting with Fano militias on January 29, as war crimes of murder and extrajudicial executions, Amnesty International said today.

Residents told Amnesty International that on the eve of the annual feast of St. Mary, observed on January 30, ENDF soldiers rounded up local men from their homes, shops and the streets and shot and killed scores. Four people who buried victims and one authoritative source provided consistent accounts of more than 50 people killed, though Amnesty International has not been able to independently verify exact numbers.

“Mass killings are becoming shockingly common in Ethiopia. Last year, UN investigators reported more than 48 “large scale killings” only in Tigray since 2020. The lack of credible efforts by the Ethiopian government to ensure justice for families of those killed and prevent such atrocities adds insult to injury,” said Tigere Chagutah, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East and Southern Africa.

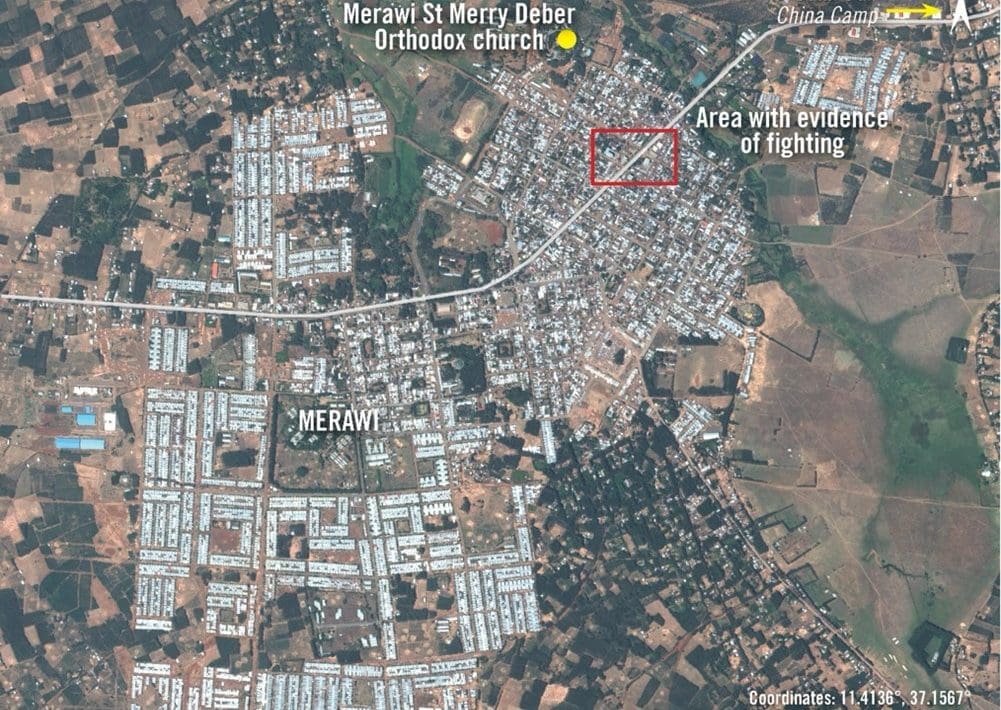

Amnesty International interviewed 13 individuals, including four relatives of victims and five people who retrieved bodies from the streets, as well as community leaders and a healthcare professional. The organization’s Crisis Evidence Lab analyzed video footage and satellite imagery to verify where the ENDF was camped, the presence of dead bodies and burned vehicles in the streets, and the timeframe for these events, which correlated with witness testimonies. On March 21, Amnesty International shared the preliminary findings with the Ethiopian government but is yet to receive a response.

All residents interviewed by Amnesty International said they woke up to the sound of gunshots and what they described as “heavy weapon explosions” on January 29 at around 5:40 am. Due to the ongoing state of emergency and a curfew on movement between 6 pm and 6 am, most Merawi residents were still in their homes, except for laborers who left home before the fighting between Fano fighters and ENDF solders began.

Around 10 am, the fighting stopped after the Fano fighters left the city said the residents. Subsequently, the ENDF soldiers started to conduct house-to-house searches and entered local breakfast shops where daily laborers were stranded.

An eyewitness, families of victims and those who buried bodies told Amnesty International that they saw that victims had bullet wounds on their heads. One video shared on social media and verified by Amnesty International’s Crisis Evidence Lab showed at least 22 bodies along the town’s main road. The video, filmed from inside a moving vehicle, showed bodies clustered at three different points along the road.

One eyewitness who travelled to Merawi to celebrate the annual St. Mary feast told Amnesty International that he saw the soldiers shooting multiple residents on the street.

“Once I arrived, I was stuck on the road near where the killings occurred due to the fighting. The sound of gunshots calmed down around 10 am, and ENDF soldiers started patrolling the area. I first saw them killing Ayana, an old man I knew as a child, for his popular big loaves of bread, locally known as anbasha. They brought him onto the street and shot him in the head,” the eyewitness told Amnesty International.

Assefa*, who lived in Merawi, told Amnesty International: ” When I left my house the next day [January 30], I saw people screaming and crying on the street, and I saw many bodies. ENDF soldiers were seated sparsely. We approached them and asked for permission to bury the bodies. One of the soldiers spoke on his radio and gave us permission.”

Abere*, another resident of Merawi city, told Amnesty International he heard [when] one of his neighbors was being taken out of his home and that after events ended, he counted 32 bodies on the streets.

“Once the fighting ended, the soldiers [ENDF] went house to house looking for Fano fighters. My neighbor was among those killed. I heard them [ENDF] warning the mother [of the victim] to stop begging them not to take her son. We heard soldiers telling her, ‘We will also shoot you; go back.’”

Another resident, Dereje*, said his brother was among the laborers who left their homes before fighting broke out: “My family and I never left our home that day [January 29]. Around 1:30 pm, I received a call from my sister-in-law and her child, checking if he [my brother] was in my house. My brother told them he was at my place to ensure they would not leave to look for him. Then, our relative called his phone, and another person picked it up. I then started making calls and learned from people who were with him that ENDF soldiers killed him and the person who sheltered him. My brother left home before the fighting started, carrying his lunchbox and tools for work,” he said.

Derebew*, a relative of a 70-year-old man who was killed, said the victim was on his way home from working as a night guard. “We were in the house, and we could not leave. Our neighbors told us that he was showing the soldiers [ENDF] his house and explaining that he was coming from work. They shot and kill him. I found his body on the street the next day.”

Motor vehicles burnt down by ENDF soldiers

ENDF soldiers burned down 11 three-wheel vehicles, locally known as Bajajs, and one motorbike in Merawi, according to three people who lost their vehicles, including one who witnessed the burning, interviewed by Amnesty International. Additionally, Amnesty International’s Crisis Evidence Lab analyzed satellite imagery of Merawi, which showed burn marks from the destroyed vehicles appearing between from January 28 and February 6. Footage verified by Amnesty International showed at least five burned vehicles on the town’s main road close to where some of the bodies had been seen.

Tefera* said his Bajaj was burned down on January 29, around midday. He said he saw one ENDF soldier carrying a lighter when the Bajajs were burning and that, the following day, one ENDF soldier admitted to him what they had done.

“I bought the Bajaj a few months ago, and I have not finished paying the loan I took out to buy it. I worked hard my entire life to buy that Bajaj. I started as a shoe shiner. Now I have nothing; I have no money even to buy food. I am alive because of the support I get from my friends. I lost everything,” Tefera told Amnesty International.

Failure to end atrocities and bring perpetrators to justice

Dereje*, whose brother was killed, told Amnesty International that he demands justice.

“We yearn for peace. The government should investigate criminals instead of resorting to massacres. The law must guide all actions. Why do they massacre those who are innocent? My brother knows nothing. He only knows how to work. Even on holidays, he takes his sheep to the field, rather than idling at home. How can a government justify massacring people under the assumption that there might be criminals among them? We live in fear,” he told Amnesty International.

Derebew*, who lost a close relative, said: “The fighting is between those who are armed. Many of us are left without parents and families. At least don’t implicate civilians.”

Despite demands for justice for past crimes and an end to ongoing violations, including from survivors and families of victims, the Ethiopian government is yet to take concrete action to end the cycle of impunity in Ethiopia.

Federal authorities stated on February 1, 2024 that “with regard to crimes committed during the war in the northern part of Ethiopia, the federal government, on its part, already took all the necessary measures. It [the federal government] also ensured the accountability of those who should be held accountable.” Coming at a time when the federal government promises a credible transitional justice process, this statement appears to close the door on any national effort for accountability.

“Claims by the Ethiopian government that accountability has already been achieved for crimes committed in the war in northern Ethiopia demonstrate lack of political commitment to genuine justice and accountability” said Tigere Chagutah.

Lack of credible national efforts for accountability led to the establishment of the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia (ICHREE) in December 2021 by the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), through an initiative led by the European Union (EU). ICHREE had a key role to play in international oversight, early warning and prevention. In October 2023, the HRC’s scrutiny of Ethiopia ended with the expiry of ICHREE’s mandate when no HRC member state came forward to table an initiative to extend the body’s mandate. The statements by the Ethiopian government in February 2024 show that the absence of international oversight has further emboldened the government.

Amnesty International calls on the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Working Group on Death Penalty, Extra-Judicial, Summary or Arbitrary Killings and Enforced Disappearances in Africa to take urgent steps to investigate alleged crimes documented here. Amnesty International further calls on the Ethiopian government to facilitate country visits by these mechanisms.

Lastly, Amnesty International calls on the HRC to resume its scrutiny of Ethiopia and take action towards a genuine justice and accountability process that meets the expectations of victims and survivors in Ethiopia.

“HRC members, particularly those from the EU, ignored Amnesty International’s and other organizations’ plea to continue the mandate of ICHREE, given the ‘acute risk of atrocity crimes in Ethiopia, including in the Amhara region,’ as stated by ICHREE itself. Ethiopians cannot wait for justice any longer. Given continued violations in Amhara region and the lack of commitment to justice nationally, UN member states should act to reinstate HRC scrutiny of the situation in Ethiopia,” said Tigere Chagutah.

Contact: [email protected]