Overview

The UN-brokered six months truce ended in October 2022. According to the UN during this six months, the casualties due to war decreased by 60%. However, during the ceasefire and after it came to an end, parties to the conflict sporadically carried out attacks on civilian areas and frontlines in Ma’rib, Hodeidah, Ta’iz and Dhale’ governorates.

All parties to the long-standing conflict in Yemen continued to commit violations of international humanitarian and human rights law with impunity. Despite a ceasefire agreement, parties to the conflict continued to carry out unlawful attacks that killed and injured civilians, interfered with their access to humanitarian aid and destroyed civilian objects. The internationally recognized government of Yemen and the Huthi de facto authorities continued to harass, arbitrarily detain, and prosecute journalists and activists for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression or because of their political affiliation. All parties perpetrated gender- based violence and discrimination. The Huthi de facto authorities banned women from travelling without a male guardian, increasingly hindering Yemeni women from working and giving or receiving humanitarian aid. All parties continued to target LGBTI people with arbitrary arrest; torture, including rape and other forms of sexual violence; threats; and harassment. All parties to the conflict contributed to environmental degradation. Death sentences have been handed down and executions carried out.

Yemenis’ access to food remained highly restricted. This was aggravated by the depreciation of the Yemeni riyal, high inflation rates and soaring global food prices. According to the World Food Program, food insecurity reached critically high levels in 20 out of the 22 governorates.

In April 2023, through a UN-brokered deal the internationally recognized government of Yemen and the Huti de factor authorities exchanged over 800 prisoners.

KEY ISSUES

All parties to the conflict continued to detain, forcibly disappear and torture individuals on the basis of their political, religious or professional affiliations, their peaceful activism or their gender. Huthi de facto authorities continued to arbitrarily detain hundreds of migrant men, women and children, mostly Ethiopian and Somali nationals, in poor conditions for indefinite periods in Sana’a city. Huthi de facto authorities continued legal proceedings targeted against Baha’i on the basis of their religion, and froze or confiscated assets belonging to 70 members of the community. They also continued to arbitrarily detain, since March 2016, a Jewish man on the basis of his religion, despite judicial rulings requiring his release.

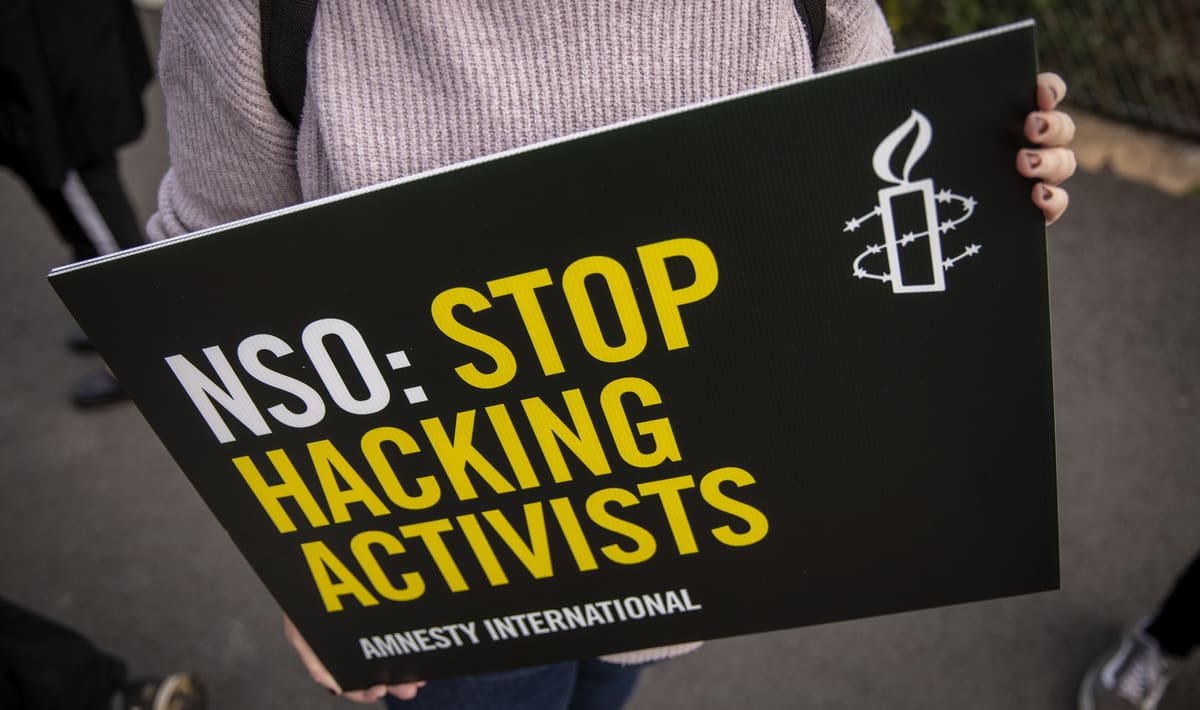

All parties continued to curtail free speech and assembly of human rights defenders, journalists, political opponents and perceived critics. In January 2022, the Huthi de facto authorities raided at least six radio stations in Sana’a and shut them down. The owner of Sawt al- Yemen radio station appealed against the closure before the Journalism and Publishing Court in Sana’a and obtained a court order in July in favor of reopening the station. On July 2022, however, security forces raided and shut down the station again and confiscated its broadcasting devices. On February 22nd, the Sana’a-based Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) – a court traditionally reserved for security-related crimes – sentenced journalist Nabil al-Sidawi to eight years in prison following a grossly unfair trial on trumped-up, serious charges including spying. On 28 June, the Hodeidah- based SCC sentenced journalists Mohammed al-Salahi and Mohammed al-Juniad each to three years and eight months in prison following secret proceedings in the absence of their lawyer on trumped-up spying charges (more hereopens in a new tab). The internationally recognized government harassed, summoned for investigation, or arbitrarily detained at least seven journalists and activists in areas under its control, including in Ta’iz and Hadramout governorates. Judicial authorities prosecuted at least three journalists for publishing content critical of officials and public institutions. Charges included “insulting” a public employee, which carries up to two years in prison, “mocking” army officials, and “offending a symbol of the state” (more hereopens in a new tab). On July 2022, security forces in Ta’iz governorate arbitrarily arrested a writer because of a social media post in which he criticized corruption in aid delivery to internally displaced people in Ta’iz governorate. Security forces held him at the security department of Jabal Habashi district for eight hours and only released him after forcing him to sign a pledge stating that he would refrain from posting any opinions on social media. In June 2022, a bomb planted in the car of Saber al-Haidari, a reporter with the Japanese state broadcaster NHK, which he was driving in the southern port city of Aden, killing him at the scene.

All parties to the conflict continued to impose and exploit patriarchal gender norms, used gender-based violence and discrimination to further their objectives, and maintained a wide range of discriminatory and oppressive customary and statutory legal provisions. The Huthi de facto authorities continued to impose their mahram (male guardian) requirement, which bans women from travelling without a male guardian or evidence of their written approval, across governorates under Huthi control or to other areas of Yemen. From April 2022, tightened Huthi restrictions increasingly hindered Yemeni women from working, especially those required to travel for their job (more hereopens in a new tab). This had a direct impact on the access of Yemeni women and girls to healthcare and reproductive health rights as Yemeni women humanitarian workers increasingly struggled to conduct fieldwork in Huthi-controlled areas and were forced to cancel field visits and aid deliveries. In March, the government’s Ministry of Interior issued a circular to facilitate Yemeni women’s access to a passport as per Yemeni law. This followed a Yemeni women-led campaign, “My passport without guardianship”, which opposed the customary practice that denies women the right to acquire a passport without the permission of their mahram. The Huthi and government authorities continued to arbitrarily detain women past completion of their sentences when they did not appear to have a male guardian to escort them home from the prison. The Huthi de facto authorities continued to detain actress and model Intisar al- Hammadi, who was sentenced in 2021 to five years in prison on charges of committing an “indecent act”. In January 2022, the government’s political security forces in Ma’arib arbitrarily arrested a woman because her brother had worked for the Huthis and she later died in custody, according to the Women’s Solidarity Network. In July and August 2021, government armed forces in Ta’iz harassed and assaulted two women human rights defenders, one of them living with disabilities, and accused them of “prostitution” as well as working for the Huthis. In September 2021, according to Mwatana for Human Rights, political security forces in Ma’arib arbitrarily detained and forcibly disappeared another woman, a human rights activist and humanitarian worker, for a month.

The security forces of the Southern Transitional Council (STC), the Huthis and the internationally recognized government continued to target people with non- conforming sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics (SOGIESC) with arbitrary arrest, torture, including rape and other forms of sexual violence, threats and harassment. The STC and the Huthis arrested at least five people and detained them on grounds of their non-conforming “feminine” or “masculine” appearance and/or behavior in public or on social media, or based on their LGBTI-rights activism. Plain clothes Security Belt forces arrested a third-gender person in the street, took him to an official facility and interrogated him on accusations of sodomy and being an agent for Security Belt enemies. The Security Belt forces then transferred the person to another official facility where a member of the Security Belt forces beat and raped him. A queer man was arrested in the street by Huthi security forces for being a “sexual deviant”. Huthi security forces detained him for several hours in a military vehicle and only released him on condition that he agree to assist in their surveillance of people with nonconforming SOGIESC. They ordered him to entrap men in sexual encounters and inform on them to the Huthi authorities. After they released him, he subsequently refused to do this. In response, Huthi security forces contacted him and his acquaintances, threatened him and told him that he was wanted for arrest.

Parties to the conflict continued to restrict movement and aid delivery, including by imposing bureaucratic constraints such as travel permit denials or delays, cancellation of humanitarian initiatives, and interference in the project design and implementation of humanitarian activities. The Huthi de facto authorities continued to close the main roads in and out of the city of Ta’iz. The closures severely inhibited the efficient movement of food, medicines and other essential goods in and out of Ta’iz governorate (more hereopens in a new tab). Throughout 2022, there was an alarming increase in attacks on aid workers and violence against humanitarian personnel assets and facilities by parties to the conflict. In the first half of the year, according to the UN Yemen office, one aid worker was killed, two were injured, seven were kidnapped and nine were detained. In the same period, there were also 27 incidents of threats and intimidation, and 28 incidents of carjacking, leading to temporary suspensions of movement and aid delivery in several governorates.

Parties to the conflict were responsible for environmental degradation across Yemen through poor governance, cancelling programming, neglect of legally protected areas, mismanagement of oil infrastructure, and placing economic pressure on civilians. Yemenis resorted to environmentally damaging coping mechanisms, including reliance on charcoal, unsustainable fishing and unsustainable development. This resulted in increased pollution, deforestation, soil erosion and loss of biodiversity, which adversely impacted enjoyment of the rights to health, food and water. According to the UN Environment Program, ambient air quality did not meet the WHO guideline levels for air pollutants that adversely impact health. The mismanagement of oil infrastructure at Bir Ali oil terminal in Shabwa governorate continued to pollute al- Rawda district. In April, damage in the oil supply pipeline polluted large areas of agricultural land and groundwater sources in Wadi Ghourayr and Ghail al Saidi areas, according to Holm Akhdar, a local environmental organization. In July 2022, a decaying oil tanker caused oil spills in the port of Aden, in Southern Yemen, further worsening the coastal and marine pollution in the area. In February 2022, Special UN envoy to Yemen announced agreement with Huthi to transfer 1.14 m barrels of oil from FSO Safer to another ship. The tanker is located 37 miles north of Yemeni port of Hodeidah. The possible risk of spilling its cargo, would have devastating consequences for the biologically sensitive Red Sea coastline, as well as water scarcity, health, and the food security and livelihoods of millions of Yemenis and Eritreans reliant on Red Sea fishing (more hereopens in a new tab). In September the UN announced that it has raised $75 million needed to start the first phase of operation. The operation expected to start offloading oil by early June 2023.

Over 78 death sentences were handed down and at least four execution took place in 2022.

Relevant Links

- 2022/2023 Amnesty International Annual Report

- 2021/22 Annual Global Report on Human Rights-Yemen

- Huthis Must End the Prosecution of Journalists and Crackdown on Media

- Joint NGO Letter: International Accountability Critical to Achieving Justice for Victims and Promoting Lasting Peace in Yemen

- Huthis ‘suffocating’ women with requirement for male guardians

- Houthis should urgently open Taizz roads

- Joint Response to Yemen’s Supertanker Crisis

- Further information: Journalist denied urgent health care: Tawfiq al-Mansouri