Overview

The government continued to commit serious human rights violations, including arbitrary detention, cruel and inhuman treatment of detainees, suppression of freedom of expression, and violation of the right to privacy. A number of detainees remained in prison past the completion of their sentences without legal justification. The UAE government continued to deprive stateless individuals of the rights to nationality, impacting their access to a range of services. Courts passed death sentences and executions were reported.

The UAE continues to be involve as a party to the conflict in Yemen, which saw a range of egregious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. It also continues its involvement with the conflict in Libya through its support for the Libyan Arab Armed Forces, which committed violations of international and human rights law. The government renewed its stance against recognizing the rights of refugees.

KEY ISSUES

The UAE was responsible for dozens of new and ongoing arbitrary detentions. The authorities refused to release at least 41 prisoners who completed their sentences during the year, bringing the total number, including those from previous years, to 48. All 41 were part of the “UAE-94” mass trial of 2012-2013. The government characterized such detentions as ongoing “counselling” for those who have “adopted extremist thought,” a procedure authorized under Articles 40 and 48 of the counter- terrorism law (Federal Act No. 7 of 2014) stated that those “adopting extremist or terrorist thought” may be held indefinitely in prison for “counselling”. The law requires the Office of Public Prosecution to obtain a court order for such detentions, but does not give the detainee the right to challenge their continued detention (more hereopens in a new tab). Most such prisoners were held at al-Razin prison in the desert south-east of Abu Dhabi city. Amnesty International has documentedopens in a new tab the cases of some of the prisoners being held past completion of their sentences since 2017. Seven of these were eventually released, and the other 17 are still in prison. Some of the individuals held after completing their sentences are Ali al-Hammadi; Shahin al-Husani; Hasan al-Jaberi; Husain al-Jaberi; Ebrahim al-Marzooqi; Sultan al-Qasimi; Salem Sahuh; Mohamed al-Siddiq; Ahmed al-Suwaidi, Ahmed al-Zaabi, Omran al-Harthi, Mohamed al-Roken. In addition to the ongoing cases of “counselling” post-sentence detention monitored by Amnesty International, the UAE has also extended two prisoners’ sentences by issuing new prison terms against them for speaking out about their prison conditions. As the Emirati government informed the UN Secretary-General’s office in 2021, it added new three-year sentences to the prison terms of Maryam al-Balushi and Amina al-Abdouli for “publishing information that disturbs the public order”, referring to voice recordings they smuggled out of prison claiming they were being held in abusive conditions. Amina al-Abdouli was originally sentencedopens in a new tab to five years in prison in 2016 for publishing Tweets that the UAE deemed offensive to its government and to other states in the region. Maryam al-Balushi was convicted in 2017 on charges of financing terrorism in Syria. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention found that both women were victims of unfair trials and that their detention is arbitrary.

In July 2022, in its first review of the UAE, the UN Committee against Torture stated its “concern that reports received detail a pattern of torture and ill-treatment against human rights defenders and persons accused of offences against state security.” Authorities held human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor in solitary confinement for the entire year and deprived him of glasses, books a bed, mattress and pillows, and personal hygiene items (more hereopens in a new tab). Such prolonged solitary confinement, especially in combination with the degrading and inhuman treatment, rises to the level of torture. In one case, authorities denied Mohamed al-Siddiq, imprisoned since 2012 for exercising his right to freedom of expression, all phone calls with his nuclear family who live abroad.

At least 26 Emirati prisoners remained behind bars because of their peaceful political criticism. They include attorneys Mohamed al-Roken and Mohammed al- Mansoori, former heads of the UAE Jurists Association (which the government took over in 2011 after the Association called for free national elections), who were convicted in the UAE-94 trial; Nasser bin Ghaith, a lecturer in economics at Sorbonne University’s Abu Dhabi branch, detained since 2015; and human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor. In April 2021, the government sentenced prisoners Maryam al-Balushi and Amina al-Abdouli to three more years in prison for “publishing information that disturb public order”, after they had released a voice recordings of their grievances abut prison conditions. The government exercised control over expression, at times censoring content in the media or cinema deemed to be immoral. In January 2023, the Office of Public Prosecution announced that it had summoned “a number” of people who had posted videos online simply reporting rocket attacks on the UAE by Yemen’s Huthi militia, warning that any reporting of such incidents on social media violates the country’s laws. In June 2022, the Media Regulatory Office banned Lightyear, a US-produced film because it depicted a same-sex kiss. Also in June, the newspaper Al Roeya, which is published by a company owned by Deputy Prime Minister Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, fired almost all its journalists and editors because the paper had reported on how Emiratis were reacting to the rising price of energy. The print newspaper then ceased publication, with the website kept online by a skeleton staff and publishing only business news. In August 2022, the Media Regulatory Office and Telecommunications and Digital Government Regulatory Authority instructed Netflix to remove same-sex content from its services in the UAE or face prosecution. The new Code of Crimes and Punishments, which went into effect on January 2nd 2023, brought in some reduction of sentences but retained overly broad provisions that criminalize free expression and assembly, and added a new clause punishing unauthorized transmission of governmental information. Article 178, a new provision, forbids transferring “without a license” any official “information” to any “organization”, which taken literally criminalizes most transmission of governmental information. Article 184 decreased the punishment for “anyone who mocks, insults, or damages the reputation, prestige or standing of the state” or “its founding leaders” from 10-25 years to a maximum of five years. Article 210 decreased the punishment for participating in any public gathering “tending to damage public security” from up to 15 years to a maximum of three years. Article 26 of the new Law on Combating Rumors and Cybercrimes, which also went into effect on January 2nd, imposes up to three years’ imprisonment on anyone who uses the internet to encourage a demonstration without prior permission from the government.

The estimated 80,000-120,000 stateless people born in the UAE continued to be deprived of equal access to rights covered for Emirati citizens at state expense, such as state-subsidized health care, housing and higher education, or jobs in the public sector. Access was dependent on proof of citizenship and stateless people were denied recognition as citizens, despite most of them having roots in the UAE going back generations. The stateless Emiratis, who have ancestral origins in East Africa, South Asia and the Arabian Peninsula, must pay to receive education and healthcare through the private market. Stateless people also had to find “sponsors” to obtain temporary residence permits, without which they are considered “illegal residents”, and are ineligible to work in the higher-paid government sector (more). Stateless Emiratis given Comorian passports under a 2008 deal between Comoron and the UAE.

Women remained unequal with men under Emirati law. Married women were obliged “to look after the house” as a “right” held by husbands under Article 56.1 of the Law on Personal Status. The Article was amended in late 2019 to remove a line stating that a husband has the right to “courteous obedience” from his wife. Article 72 continued to allow judges to determine whether a married woman was permitted to leave the house and to work. Transmission of nationality continued to be granted on a gender-preferential basis, meaning that children of Emirati mothers did not automatically receive nationality and were recognized as nationals only at the discretion of the federal cabinet. In September 2021, the UAE annulled Article 334 of the Penal Code, which had made “honor” killings punishable by as little as one month in jail.

In September 2022, the government directed schools across the UAE to ensure that teachers “refrain… from discussing gender identity, homosexuality or any other behavior deemed unacceptable to UAE society” in classrooms. Since 2021 there have not been any documented prosecutions of consensual sexual acts under Article 356 of the Penal Code. However, vague language criminalizing “scandalous act(s) offending modesty” remained under Article 358 of the Penal Code

The sponsorship (kafala) system for employing migrant workers in the UAE – alongside unsanitary living conditions in overcrowded accommodations, scarce legal protection and limited access to preventive health care and treatment. On the night of 24-25 June 2021, police in Abu Dhabi broke into the homes of hundreds of migrant workers as they slept, targeting Black Africans in racially motivated arrests, detained them for weeks in al-Wathba prison and subsequently deported them without due process. While in detention, the authorities in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) subjected them to inhuman and degrading treatment and stripped them of nearly all their belongings. These African workers were living and working in the UAE legally.

Courts continued to issue new death sentences, primarily against foreign nationals for violent crimes. No execution recorded in 2022.

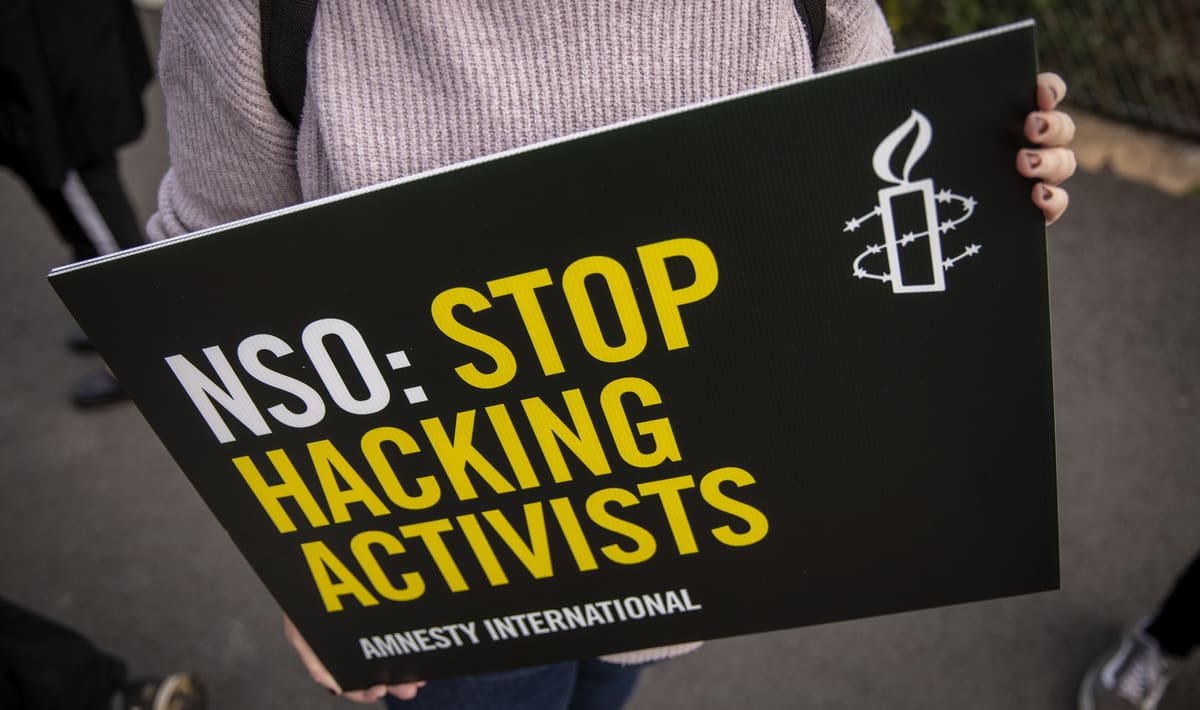

In July 2021, UAE revealed as one of 11 countries that were clients of NSO Group, a company specialized in cyber surveillance. Amnesty International as part of the Pegasus project, found that Pegasus had been used to hack devices of several Emiratis and foreigners, including Emirati prime minister ex-wife and her two lawyers, Emirati dissident Alaa al-Siddiq (who died in a car crash in UK last year), and a UK national David Haigh.

The UAE raised oil production, contrary to the UN conclusion that countries must begin reducing production to meet their obligations under the Paris Agreement on climate change, to which the UAE is a party. According to World Bank data, the UAE has one of the world’s top five highest levels of per capita carbon dioxide emissions.