The following information is based on the Amnesty International Report 2021/22. This report documented the human rights situation in 149 countries in 2021, as well as providing global and regional analysis. It presents Amnesty International’s concerns and calls for action to governments and others.

INDONESIA 2021

Human rights defenders, academics, journalists and students were among those prosecuted and harassed for their legitimate activities. The Electronic Information and Transaction Law was widely used to restrict the right to freedom of expression online. Political and labour rights activists and Indigenous peoples were among those arrested and prosecuted, including for participating in peaceful protests, and excessive force was used to disperse protesters. At least 28 prisoners of conscience remained imprisoned. Security forces committed unlawful killings in Papua and West Papua, largely with impunity. There was a continued pattern of discrimination against members of the Ahmadiyya religious community.Background

A sharp increase in Covid-19 infections in mid-2021 threatened access to healthcare, with many hospitals unable to provide beds or oxygen for treatment. Economic challenges and dissatisfaction with the government’s response to the pandemic contributed to growing discontent and increased public protest.Human rights defenders

At least 158 physical assaults, digital attacks, threats and other forms of attack against 367 human rights defenders were reported during the year. In February, father and son Syamsul Bahri and Samsir from the Nipah Farmer community in North Sumatra province were accused of assault, arrested, and detained for 14 days following an incident in December 2020 when Syamsul Bahri, the community chairman, questioned two people who were taking photographs of them working on a mangrove rehabilitation project in the area. Local NGOs believed that the assault charges were linked to the men’s activities to conserve and defend access to their community lands. They were convicted on 31 May and sentenced to two months’ suspended prison sentence and four months’ probation. On 18 August, the Medan High Court upheld the ruling after an appeal by the prosecutor seeking the imprisonment of Syamsul Bahri and Samsir.1 They remained under probation at year’s end. On 17 May, following their public criticism of the dismissal of 75 employees of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), Busyro Muqoddas and Bambang Widjojanto, both former KPK commissioners, and at least six members of the NGO Indonesian Corruption Watch (ICW), reported that unidentified parties had hacked their messaging app accounts. The hacks occurred ahead of an ICW press conference criticizing the dismissals, which was also disrupted by spam intrusions and other digital interruptions.2Indigenous peoples’ rights

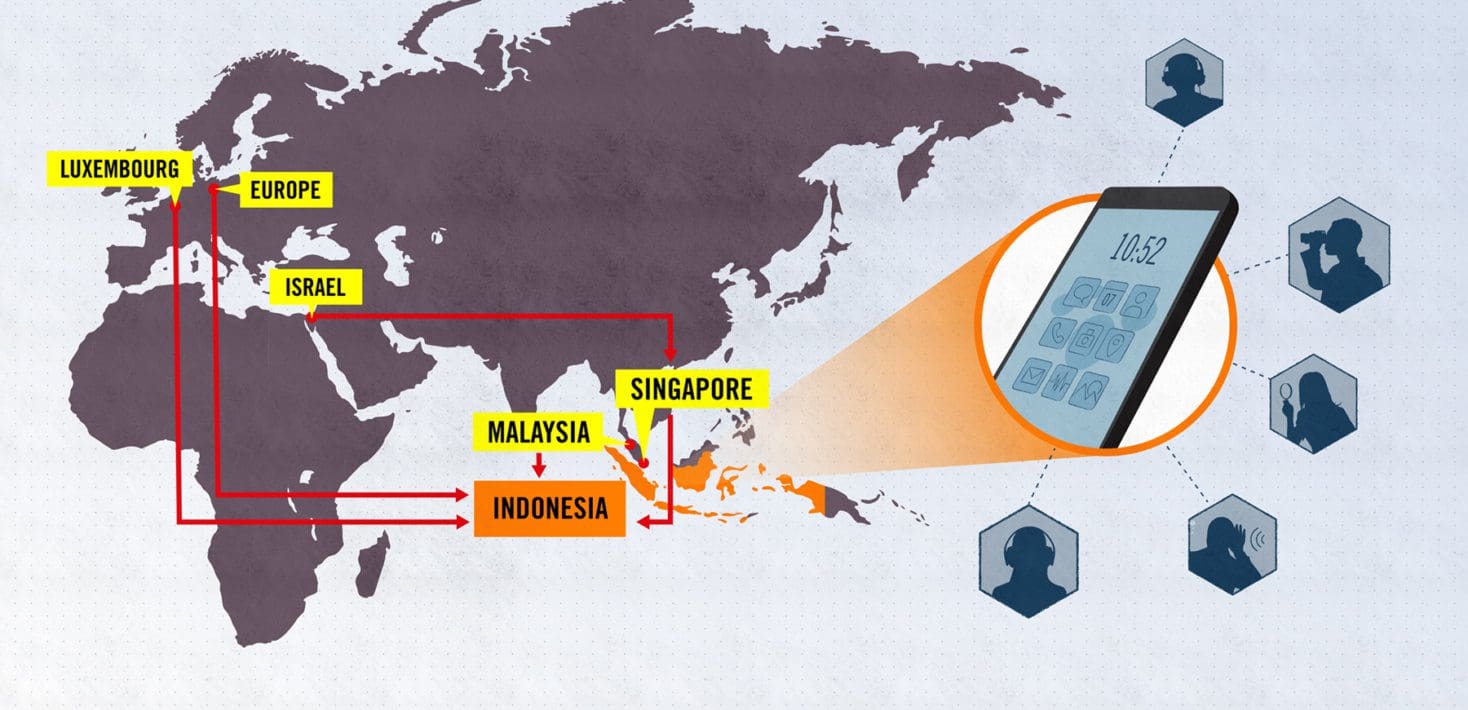

There was an ongoing pattern of violence and intimidation throughout 2021 towards Indigenous peoples seeking to protect their lands and traditions from commercial activities. On 27 February, three leaders of the Dayak Modang Long Wai Indigenous people in East Kalimantan province were arrested during a protest against a palm oil plantation company that was operating on their customary lands. In April, members of the Sakai Indigenous people in Riau province were met with violence when attempting to stop eucalyptus trees being planted on their lands by private security officers employed by a timber company with which they had a longstanding dispute over land rights. Community members attempting to block the operation were pushed, dragged and thrown to the ground by the security officers. In a similar incident in May, members of the Huta Natumingka Indigenous people in North Sumatra province were violently assaulted when protesting against the arrival of hundreds of private security officers sent by a pulp and paper company to plant eucalyptus trees on the land they inhabited. Dozens of community members suffered injuries in the two incidents.Freedom of expression

Authorities continued to limit the right to freedom of expression both online and offline. The Electronic Information and Transaction (EIT) Law was used against individuals for their legitimate criticisms of official policies or actions in at least 91 cases involving 106 victims. These included Saiful Mahdi, a lecturer at the Syiah Kuala University in Aceh province, who began a three-month prison sentence on 2 September after being found guilty of criticizing the university’s hiring process in a WhatsApp group in 2019. He was released on 12 October after being granted an amnesty by the president. On 22 September, the coordinating minister for maritime and investment affairs accused Haris Azhar and Fatia Maulidiyanti of “spreading false information” in connection with a YouTube video they hosted in August 2020 in which they reported allegations that the minister and members of the military were involved in the mining industry in Papua. The two video hosts were sent subpoenas on 26 August and 2 September by the minister under the EIT Law and faced criminal investigation. In August, the police interrogated several individuals suspected of making murals and posters featuring messages critical of the government that appeared in several cities.3 On 13 September, at least seven students of Universitas Sebelas Maret in Surakarta in Central Java were arrested after unfurling posters during a visit to the campus by President Widodo. The posters contained appeals to the president to support local farmers, address corruption and prioritize public health during the pandemic.4Freedom of association and assembly

Authorities continued to arbitrarily arrest and detain political activists in the regions of Papua and Maluku where there was a history of pro-independence movements. At year’s end, at least 15 Papuan prisoners of conscience and 11 from Maluku were still imprisoned. All were charged with or found guilty of makar (rebellion) provisions of Indonesia’s Criminal Code. On 9 May authorities in Jayapura, the capital of Papua, arrested Papuan pro-independence activist Victor Yeimo who was peacefully protesting against racial discrimination. He was charged with violating Article 106 on treason and Article 110 on conspiracy to commit treason under the Criminal Code. His trial was pending at the end of the year. Individuals supporting workers’ rights were detained. On 22 February, Aan Aminah, the head of the Militant Trade Unions Federation, was detained on charges of assault, which carries a prison sentence of up to two years and eight months. The charge related to an incident in June 2020 when Aan Aminah had been attempting to speak to company bosses about the termination of contracts of several workers when she defended herself against forcible removal by security guards.5 She was acquitted on 6 July, but the prosecutor appealed against the decision. No decision had been made on the appeal by the end of the year. On 1 May, police arrested dozens of students who were participating in peaceful protests to mark International Labour Day in the capital, Jakarta, and the city of Medan. The police reportedly claimed that only manual workers were permitted to take part in Labour Day events.Excessive use of force

Peaceful protests against the renewal of and revisions to the Special Autonomy Law for Papua, passed by Indonesia’s House of Representatives on 15 July, were met with disproportionate force including beatings, water cannon and baton rounds. Protests took place in Jakarta and Papua against the extension of the special autonomy status of Papua, and against new provisions introducing additional central government powers over Papuan affairs and removing the right of Papuans to form political parties. On 14 July, at least four students were injured in Jayapura after clashes with security forces. Police reportedly beat protesters using their fists, guns and rubber batons. On 15 July, police dispersed protesters in front of the House of Representatives building in Jakarta. At least 50 people were arrested. One protester described being beaten, punched, stamped on and racially abused by members of the security forces before being pulled into a truck and taken to the Jakarta police headquarters. On 16 August, during another protest in Jayapura, security forces used water cannons, rubber batons, and baton rounds to disperse protesters.Unlawful killings

There were reports of 11 incidents of suspected unlawful killings by security forces involving 15 victims during the year. All took place in Papua. Five involved members of the Indonesian military, two were attributed to the police, and four implicated both military and police officers. Authorities claimed that they had initiated investigations into four of the 11 incidents, but no one had been brought to justice in connection with any of the killings by the end of 2021. On 4 June, Denis Tabuni and Eliur Kogoya were shot by a member of the military in a market in the town of Wamena in Jayawijaya Regency. Denis Tabuni died and Eliur Kogoya sustained a gunshot wound to his leg. Instead of an investigation, a “peace agreement” was signed between the alleged perpetrator and Eliur Kogoya’s family.6 On 16 August, police shot dead Ferianus Asso who was participating in a protest in Yahukimo Regency, Papua, to demand the release of Papuan pro-independence activist Victor Yeimo.Workers’ rights

The disbursement of incentive payments to health workers in recognition of their work during the Covid-19 pandemic was delayed by data inconsistencies and bureaucratic hurdles. The incentive system was introduced in March but as of July at least 21,424 health workers across 21 provinces had experienced delays or even cuts to payments to which they were entitled. According to LaporCovid-19, an independent citizen-based reporting platform, many health workers had to go in person to the Ministry of Health in Jakarta to ensure that their data was accurately recorded; this was not always possible, especially for those working in more remote areas.7 A former volunteer health worker at the Wisma Atlet Emergency Hospital in Jakarta was subjected to intimidation by the security forces after planning a press conference to publicize delays in the delivery of incentive payments. She said that she was interrogated for approximately five hours by security forces on 7 May in a hospital committee room.Freedom of religion and belief

The Ahmadiyya religious community continued to face discrimination and its members were denied the right to carry out religious activities in several provinces. In Sintang Regency, West Kalimantan province, local authorities issued a “Joint Agreement Letter” on 29 April forbidding the local Ahmadiyya community from practising their religion. On 13 August the Ahmadiyya mosque was closed down following pressure from a local Islamist group. The following month, a group of unidentified assailants attacked the mosque and burnt down an adjacent building. Authorities who were present took no action to prevent the attack.8 On 6 May, police officers stopped construction work on an Ahmadiyya mosque in Garut Regency, West Java province, and sealed off the site. The action was reportedly taken under an order from the Garut Regent following protests from local residents.9 Ahmadiyya community representatives were excluded from discussions between the local leaders and residents prior to the work on the mosque being halted. Their request to discuss the issue with the police was also rejected.Relevant Links

- Indonesia: Further information: Environmental Human Rights Defenders Free: Syamsul Bahri and Samsir (ASA 21/4871/2021), 12 October

- “Indonesia: Hacking the accounts of anti-corruption activists is a form of stifling freedom of expression”, 18 May (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Freedom of expression: 404 not found”, 20 August (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Excessive, police action arrests poster bearers”, 14 September (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Bandung – Free the head of Sebumi Federation Aan Aminah”, 25 February (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Unlawful killings cannot be solved only by peace agreement”, 25 June (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Ensure health workers are paid on time and in full as Covid crisis continues”, 6 August

- “Indonesia: The state must protect Ahmadiyya citizens in Sintang”, 3 September (Indonesian only)

- “Indonesia: Repeal joint ministerial decree and protect Ahmadiyya’s rights”, 7 May (Indonesian only)

- For more information visit the Amnesty.org Country page