China’s top legislature unanimously passed a national security law for Hong Kong on June 30, 2020 and the new law entered into force in the territory the same day, just before midnight. The Chinese authorities forced the law through without any accountability or transparency: it was passed just weeks after it was first announced, bypassing Hong Kong’s local legislature, and the text was kept secret from the public and allegedly even the Hong Kong government until after it was enacted.

The 2020 National Security Law (NSL) and other repressive laws were widely used to target people exercising their rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association. The UN Human Rights Committee urged the Hong Kong government to repeal the NSL and sedition provisions of the Crime Ordinance, and in the meantime to refrain from applying them.

There have been numerous crackdowns against pro-democracy activists, journalists, human rights defenders and others by the Hong Kong authorities. Many individuals were detained and/or sentenced to prison.

Amnesty International is insisting that Hong Kong authorities strictly adhere to their human rights obligations in implementing the NSL and that the international community hold them to account. The Hong Kong government should not sacrifice the freedoms that have distinguished the city from mainland China.

Amnesty International urges the Hong Kong police to adopt a less confrontational approach to demonstrations and facilitate the right to peaceful protest. Amnesty also calls for a thorough and independent investigation into unnecessary and excessive use of force by police at protests.

Key Issues

In March 2024, Hong Kong’s Legislative Council (LegCo) unanimously voted to pass the Safeguarding National Security Ordinance under Article 23 of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution.

Article 23 of the Basic Law requires the government to pass local laws to prohibit seven offenses: treason, secession, sedition, subversion against the Central People’s Government, theft of state secrets, to prohibit foreign political organizations or bodies from conducting political activities in the territory, and to prohibit political organizations or bodies of the territory from establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.

The Ordinance contains many troubling provisions, such as the vague and broadly worded crime of ‘external interference’, which could lead to the prosecution of activists for their exchanges with foreign actors. Meanwhile, the right to a fair trial comes under increasing attack with new investigatory powers allowing for detention without charge for 16 days and denial of access to a lawyer.

Amnesty recognizes that every government has the prerogative and duty to protect its citizens and all others subject to its jurisdiction, and that some jurisdictions have specific security concerns. But these may never be used as an excuse to deny people the freedom to express different political views and to exercise their other human rights as protected by international human rights law and standards.

At least 11 people were sentenced to terms of imprisonment during the year under colonial-era sedition laws for exercising their right to peaceful expression.

In September 2022, five speech therapists were sentenced to 19 months’ imprisonment each after being found guilty of sedition for publishing children’s books depicting the government’s crackdown on 2019 pro- democracy protests and other issues.

In October 2022, radio show host and public affairs commentator Edmund Wan (known as Giggs) was sentenced to 32 months in prison for “sedition” and “money laundering” for criticizing the government and raising funds for school fees for young Hong Kong activists who had fled to Taiwan after the 2019 protests. Giggs, who was detained for 19 months prior to his conviction, was released on 18 November but was required to hand over fundraising proceeds to the government. Political activists, journalists, human rights defenders and others charged under the NSL were held for prolonged pretrial detention. As of 31 October, at least 230 people had been arrested under the NSL since its enactment in 2020.

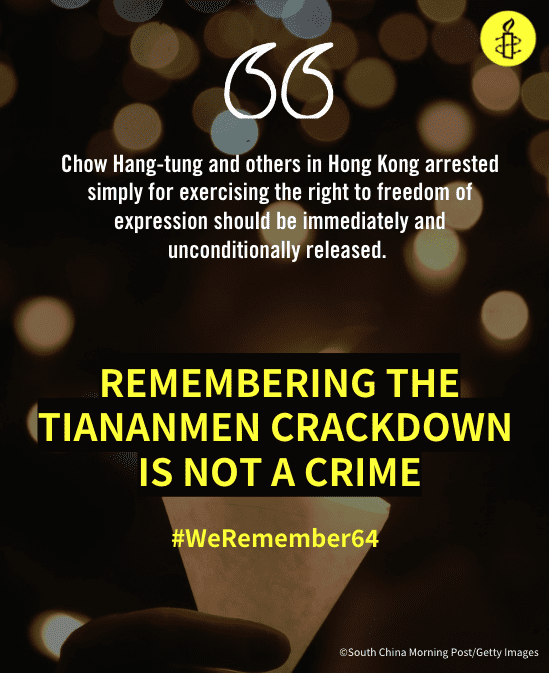

The space for peaceful protest remained highly restricted and those who participated in demonstrations or encouraged others to do so risked prosecution. In January, Chow Hang-tung was convicted of “inciting others to take part in an unauthorized assembly” and sentenced to 15 months’ imprisonment after publishing a social media post in 2021 encouraging people to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. In December, Chow Hang-tung won her appeal against that conviction, but remained in prison awaiting trial on similar charges under the NSL for which she faced up to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Authorities continued to criminalize or otherwise prevent legitimate civil society activities. Repressive legislation, including the NSL and Societies Ordinance, which gave excessive powers to the police to refuse, cancel the registration of or prohibit a society, were used with chilling effects on civil society organizations. More than 100 civil society organizations had been forced to disband or relocate since the enactment of the NSL in July 2020.

Restrictions were imposed on smaller, more informal groups. In June 2022, police reportedly delivered letters to at least five representatives of small civil society groups, including informal Facebook groups and religious networks, warning them to register or risk violating the Societies Ordinance. Five former trustees of the 612 Humanitarian Relief Support Fund, set up to assist participants in the 2019 protests with legal fees and other costs but which closed in 2021, were arrested in May, as well as the former secretary in November, for “colluding with foreign forces” under the NSL. They faced up to 10 years’ imprisonment. In December, all six were found guilty of failing to register the fund under the Societies Ordinance and fined between HKD 2,500 and 4,000 each (approximately USD 321-513).

Attacks on groups operating outside Hong Kong also expanded. In March 2022, the National Security Police sent a letter to the Chief Executive of a UK-based organization, Hong Kong Watch, accusing the group of “jeopardizing national security” by “lobbying foreign countries to impose sanctions” and engaging in “other hostile activities”. The group was accused of violating Article 29 of the NSL which criminalizes “collusion with foreign forces” and asserts extraterritorial jurisdiction. Police also blocked Hong Kong Watch’s website in Hong Kong.

Civil society organizations exercised self- censorship in order to be able to operate and raise funds. Local payment and crowdfunding platforms suspended the fundraising accounts of two groups. One of the platforms told a group that it had taken this action because of the “excessive risks involved” in hosting the account. In a separate case, three activists who had sued the Hong Kong police for ill-treatment during a land rights protest in 2014 reported that their account on an international crowdfunding platform had been removed because it was considered too high risk for the company.

Solidarity Action for Chow Hang-Tung

Chow Hang-tung, a lawyer in Hong Kong is currently imprisoned for encouraging people on social media and joining a peaceful candlelight vigil to commemorate the Tiananmen crackdown. In addition, Chow was charged for “inciting subversion” under the National Security Law on September 9, 2021 and faces potential 10 years’ imprisonment. On May 28, 2024, six individuals, including Chow Hang-tung, were arrested under Article 23 (Safeguarding National Security Ordinance) for allegedly committing offenses in connection with seditious intention. A government press release stated that the arrests were related to social media posts commemorating “a sensitive day” (referring to June 4, the anniversary of the Tiananmen crackdown).

Relevant Links

- Solidarity Action for the people of Hong Kong: Virtual Lennon Wall

- Take Action: Protect the memory of the Tiananmen Square crackdown

- Hong Kong: National anthem football arrests are an attack on freedom of expression

- Hong Kong: Opposition figures convicted in ‘ruthless purge’ of 47

- Hong Kong: Arrests under new national security law a ‘shameful attempt’ at suppressing peaceful commemoration of Tiananmen crackdown

- What is Hong Kong’s Article 23 law? 10 things you need to know

- Hong Kong: Passing of Article 23 law a devastating moment for human rights

- Hong Kong: Article 23 legislation takes repression to ‘next level’

- Hong Kong: Transgender activist must not be deported to mainland China

- Hong Kong: Submission highlights concerns with proposed Article 23 legislation

- ‘I yearn to see you’ – Valentine’s letters to activists detained in mainland China and Hong Kong

- Hong Kong: Article 23 legislation a ‘dangerous’ moment for human rights

- Hong Kong: Overturning of Chow Hang-tung Tiananmen acquittal another blow to rule of law

- Hong Kong: Jimmy Lai’s sham trial a further attack on press freedom

- Hong Kong: Absurd cash bounties on overseas activists designed to sow fear worldwide

- Hong Kong: Release activists arrested for expressing concerns about elections

- Hong Kong: ‘Absurd’ attempt to ban protest song a clear violation of international law

- Hong Kong: Tiananmen anniversary arrests highlight deepening repression

- Hong Kong: Arrests for possession of ‘seditious’ children’s books a new low for human rights

- Hong Kong: First ‘authorized’ protest since 2020 comes amid worsening crackdown on dissent

- Hong Kong: Submission to the UN Human Rights Committee 135th Session

- AI Report: Hong Kong: In the Name of National Security

- Hong Kong’s national security law: 10 things you need to know

- AI Report: Hong Kong: Missing Truth, Missing Justice