The following information is based on the Amnesty International Report 2022/23. This report documented the human rights situation in 149 countries in 2022, as well as providing global and regional analysis. It presents Amnesty International’s concerns and calls for action to governments and others.

Overview

The government continued to stigmatize feminists and human rights defenders who protested against government inaction on gender-based violence and, in some states, security forces violently repressed women protesters. Killings of journalists remained at record levels; many of the victims had been granted official protection measures. By the end of the year, more than 109,000 people were registered as missing and disappeared. The militarization of public security increased and legislation cemented the involvement of the armed forces in public security tasks until 2028. The National Guard used excessive force in several of its operations. A lack of transparency, accountability and access to information hindered access to truth, justice and reparations for victims of human rights violations and their families.

Background

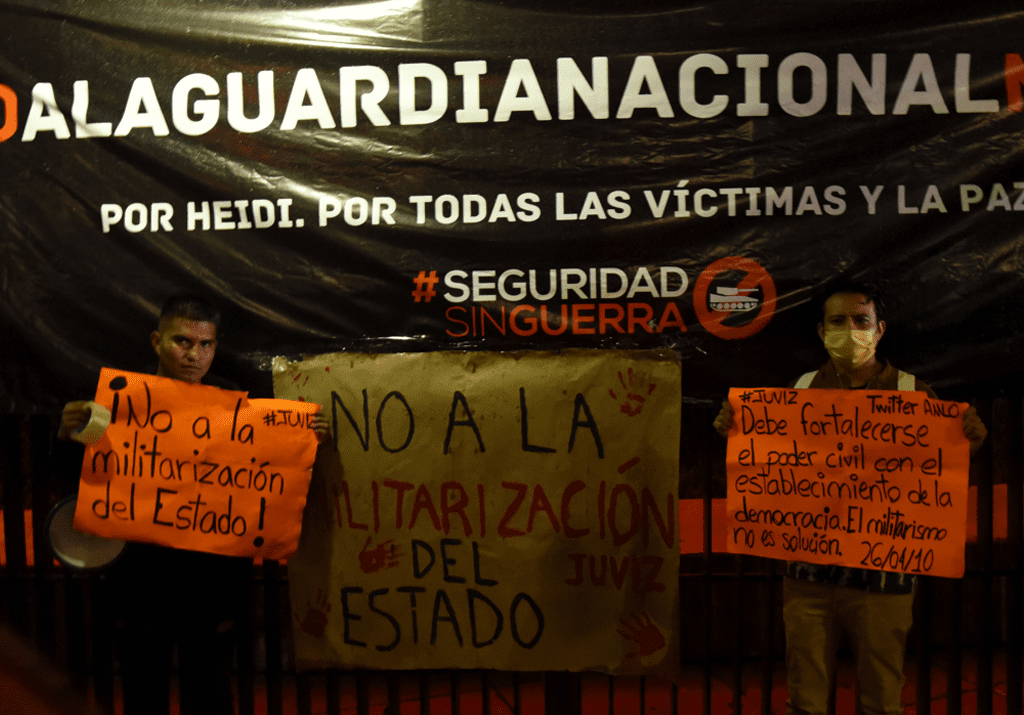

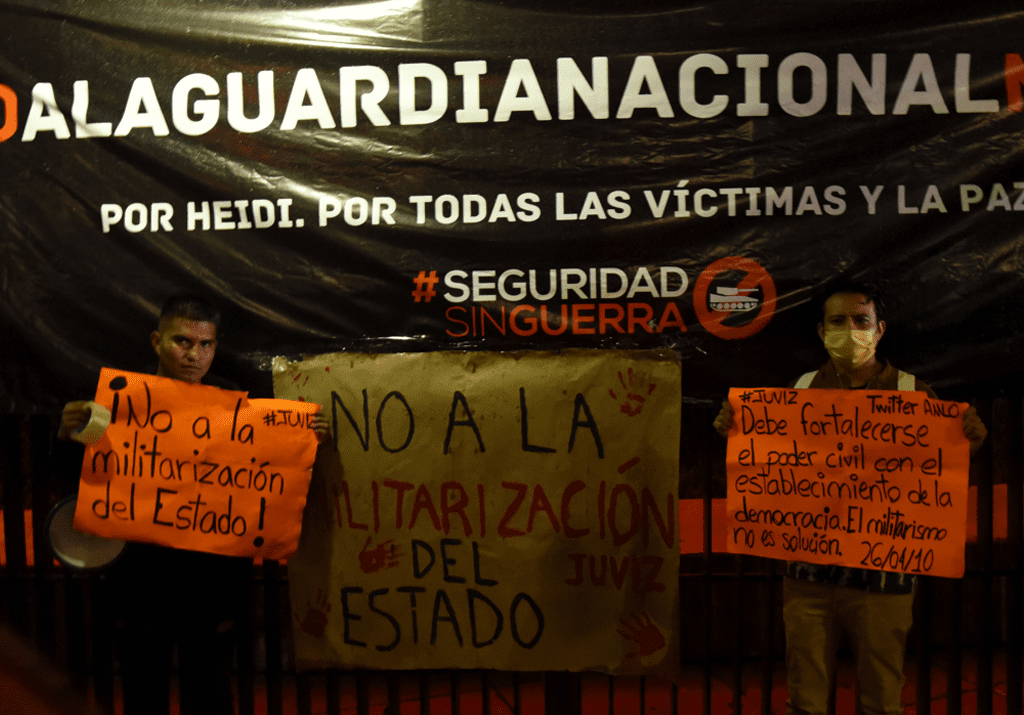

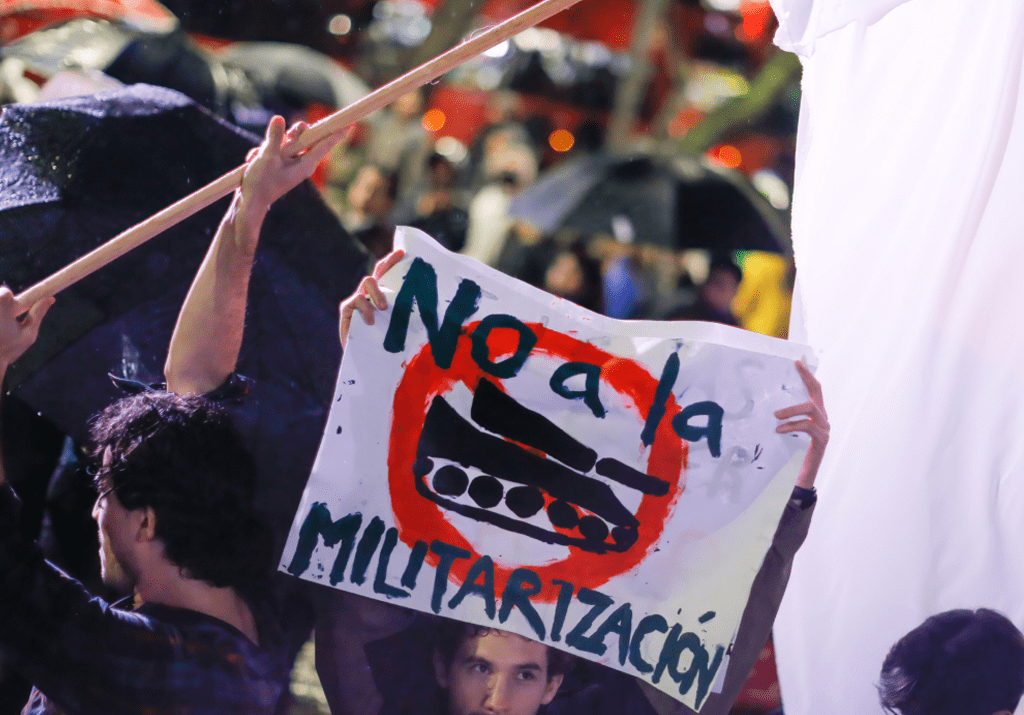

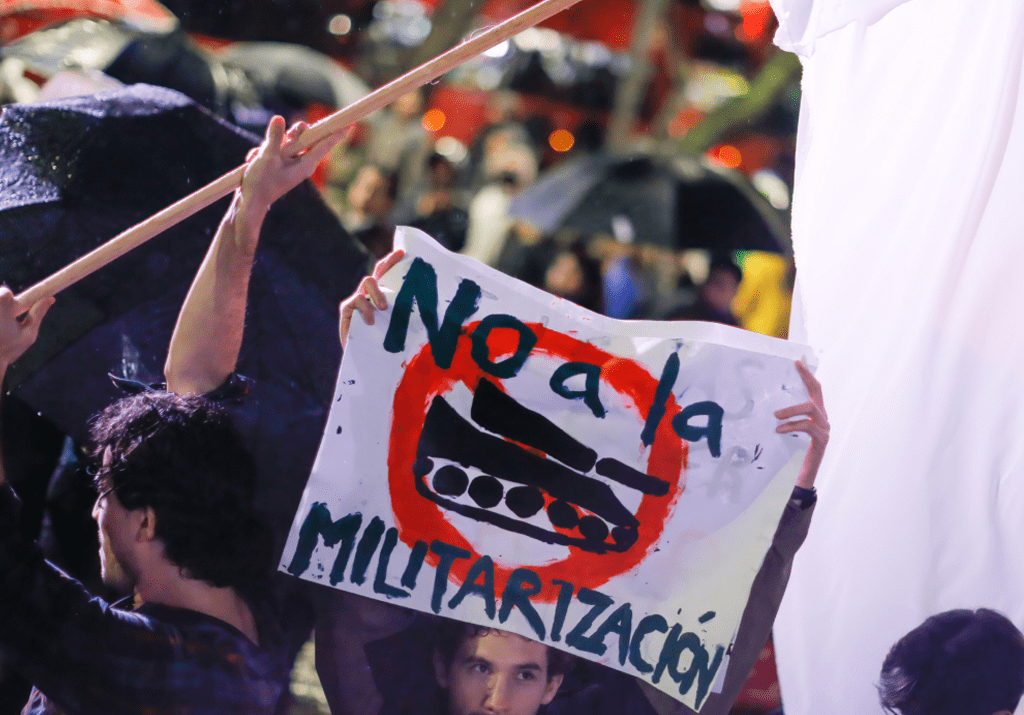

Mexican military forces often failed to protect the right to life and security of all people. The military have been involved in public security operations for 16 years and during that time the country has seen a significant increase in homicides. The National Guard and the Ministry of Defence (SEDENA) were among the 10 federal institutions which received the highest number of complaints for human rights violations during the year. The National Human Rights Commission received 476 complaints against the National Guard and 404 against SEDENA regarding multiple crimes under international law and human rights violations, including torture, killings, enforced disappearances and arbitrary detentions. In September, Congress approved the National Guard’s incorporation into SEDENA. However, in October, a federal judge suspended this decision. Congress also approved the extension of a provision giving the armed forces a role in public security operations until 2028. These decisions were promoted by the government and supported by Congress, without civil society participation.1 Civil society organizations, human rights activists and families of the disappeared took to the streets to protest against the increasing militarization of the country. As of 2022, the National Guard was responsible for 227 areas normally within the remit of civilian bodies, of which 148 were not related to public security, such as the construction of airports and highways, management of Covid-19 vaccination and migration enforcement. In November, the Supreme Court ruled that a May 2020 Presidential Decree allowing the permanent participation of armed forces in public security operations until 2024 was constitutional. Similar cases relating to the unconstitutionality of the National Guard Law and the participation of the armed forces in public security were pending before the Mexican Supreme Court at the end of the year.2

Key issues

The year proved the deadliest in history for the national press. At least 13 journalists were killed with a possible connection to their work. Many cases remained without proper investigations and the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists continued to fall short of its goal to safeguard the lives and safety of these groups. In his morning press conferences, the president expressed strong criticisms of journalists and civil society organizations that had questioned government actions, accusing them of being “conservatives” and “opponents”. The day before International Women’s Day, the president publicly stated that feminist protesters were preparing with hammers, torches and Molotov cocktails and that this “does not aim for the defence of women, they are not even feminist, participants are conservatives against our transformation policy”. In April, armed police and plain clothes policemen beat women who were protesting at the Chimalhuacán Public Prosecutor’s Office in Mexico State. The protesters were demanding sanctions against three police officers who beat and detained an activist and human rights defender. She was kept in incommunicado detention for two hours. The police also sprayed tear gas at the women outside the office. National Guard officers were present and failed to act to protect the protesters. In May, protesters from a variety of organizations and feminist movements gathered in the city of Irapuato, Guanajuato State, to peacefully protest against gender-based violence, including feminicides and disappearances of women. Police officers beat and arbitrarily detained at least 28 protesters.

Between January and November, 3,450 women were reported to have been killed; 858 of the killings were investigated as feminicides, equivalent to an average of 2.5 per day. The states with highest rates of reported feminicides were Mexico State (131), Nuevo León (85) and Mexico City (70). Structural violence against women continued to undermine women’s rights to live a life free of violence and in a safe environment without fear. In January, a judge in the municipality of Nezahualcóyotl, Mexico State, convicted a man of the feminicide of Diana Velázquez in 2017. However, authorities failed to ensure effective investigations to determine other alleged perpetrators in the case. In February, in response to a conflict of interest and lack of due diligence on the part of the San Luis Potosí State Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Federal Attorney General’s Office (FGR) took over the investigation into the feminicide of Karla Pontigo, who was killed in 2012. The State Governor of San Luis Potosí failed to meet Karla Pontigo’s mother, despite her repeated requests. In November, the Mexico State Public Prosecutor’s Office cancelled for the third time the public apology in which he promised to recognize the lack of due diligence in the investigations into the feminicides of Nadia Muciño Márquez, Diana Velázquez Florencio, Daniela Sánchez Curiel and Julia Sosa Conde.3 Excessive use of force In April, in the city of Irapuato, Guanajuato, a National Guard officer shot at a car in which students from Guanajuato University were travelling, killing one student and seriously injuring another. In August, in the city of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas State, National Guard officers shot at a car in which a woman was travelling with two children. One of the children, four-year-old Heidi Mariana, was killed and her seven-year-old brother, Kevin, was injured. In October, National Guard officers shot live ammunition in the air to disperse a peaceful protest in Jalisco State.

During the year, authorities registered at least 9,826 cases of missing and disappeared persons, of whom 6,733 were men and 3,077 were women. This brought the total number of reports of people missing and disappeared in Mexico between 1964 and the end of 2022 to over 109,000. Impunity largely prevailed on this issue; according to the Mexican Search Commission, there had been just 36 convictions for the crime of disappearance. In 2022, the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances published a report in which it highlighted the forensic crisis in the country; the bodies of more than 52,000 people in the custody of the state authorities had yet to be identified.

In August, the Mexican government presented the report of the Commission on Access to Truth and Justice (Covaj) on the case of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa who disappeared in 2014. Covaj recognized that the disappearance of the students was a state crime involving the criminal group Guerreros Unidos and Mexican government officials, including members of the armed forces. In September, Omar Gómez Trejo, the lead prosecutor for the Attorney General’s Office’s Special Unit for Investigation and Litigation on the Ayotzinapa Case (UEILCA), resigned citing undue interference by the FGR, which withdrew 21 of the arrest warrants requested, 16 of which were against military personnel.

The Independent Group of Experts (GIEI) of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which monitors progress in the Ayotzinapa case, criticized this interference, as well as the audit initiated by the FGR on 5 September regarding the work of the UEILCA. Rosendo Gómez Piedra was appointed as the new lead prosecutor for the UEILCA, despite the lack of support for his appointment from families of the victims and civil society organizations.4 In August, the Under-Secretary for Human Rights, Population and Migration announced the creation of the National Centre for Human Identification to support investigations related to disappearances and assist public prosecutors and attorneys. In October, a federal judge resolved an amparo petition filed by the human rights organization Centro Prodh ordering the creation of a national forensic database in 40 days, one of the measures pending since the approval of the Federal Law on Enforced Disappearance in 2017.

During the year, at least three mothers searching for their disappeared children were killed. In October, Rosario Lilián Rodríguez Barraza and Blanca Esmeralda Gallardo were killed in Sinaloa and Puebla States, respectively, and in November, María del Carmen Vázquez was killed in Guanajuato State.

In August, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights held a public hearing regarding the case of Daniel García Rodríguez and Reyes Alpízar Ortiz, who had been held in pretrial detention for more than 17 years. A ruling in the case was expected in 2023. In November, the Supreme Court struck down automatic pretrial detention for the crimes of tax fraud, smuggling and tax evasion via fake invoices. Another case relating to the constitutionality of automatic pretrial detention was pending at the end of the year. In December, the Supreme Court ordered the immediate release of Gonzalo García, Juan Luis López and Héctor Muñoz after seven and a half years of arbitrary detention in Tabasco State. The Court considered that their rights to presumption of innocence and due process had been violated.

According to the National Registry for the Crime of Torture, there were 1,840 reports of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment by agents of the state between January and September. This brought the total number of reports since 2018 to 14,243. The states with the highest numbers of reported cases were Mexico City, Chihuahua and the State of Mexico. However, the actual number of cases was believed to be much higher because over 93% of all crimes in the country are not reported, according to the National Survey on Victimization and Perception of Public Safety of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography. One reason for this significant under-reporting is that the majority of reported crimes go unpunished.

Human rights defenders continued to be subjected to threats, stigmatization, unjust imprisonment, torture and killings. Some of the families of human rights defenders were also threatened. Women human rights defenders were additionally subjected to sexual violence. At least 10 human rights defenders were killed during the year. A report published in 2022 by the NGO Global Witness stated that 54 defenders of the land and environmental activists were killed in 2021, making Mexico the deadliest country in the world for those defending these rights. In March, in a public statement, the president referred to European parliamentarians as “sheep” following a statement by the European Parliament highlighting attacks on and killings of human rights defenders in Mexico. In March, environmental rights defender Trinidad Baldenegro was killed in the town of Coloradas de la Virgen, Chihuahua State. He was the latest member of the Rarámuri Indigenous people to be killed for their human rights work; previous victims included Julián Carrillo, who was killed in 2018. In June, three people were killed in a church in the town of Cerocahui, Chihuahua State, among them Javier Campos Morales and Joaquín Mora, both priests and human rights defenders who had worked to defend the rights of Indigenous peoples in the Sierra Tarahumara. In October, new cases of the use of Pegasus spyware came to light, this time against two journalists, a human rights defender and an opposition politician. These latest findings indicated that there were contracts between SEDENA and companies linked to previous sales of Pegasus. In response to these reports, the president claimed that the government carried out intelligence work, which was not spying. In the same month, Guacamaya, a group of digital activists leaked information from various servers belonging to the armed forces revealing monitoring of the activities of civil society and human rights organizations, including Amnesty International.

In October, same-sex marriage was legalized in Tamaulipas State, making same-sex marriage legal in all 32 states in Mexico. Sexual and reproductive rights Four more states decriminalized abortion during the year, bringing to 11 the number of states in which abortion is legal: Baja California, Baja California Sur, Ciudad de México, Coahuila, Colima, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Sinaloa and Veracruz.

In November, Mexico updated its NDCs target of 22% to a 35% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. During COP27, Mexico announced new commitments to address the climate crisis, including doubling the production of clean energy adding 105 gigawatts. In May, a federal judge suspended the construction of Section 5 of the Mayan Train, stating that it endangered biodiversity and the land rights of Indigenous peoples who depend on the fragile ecosystems of the Mayan jungle. Despite this, the president categorized the project as one of national security, enabling the construction to continue.

The National Migration Institute received the third highest number of complaints of human rights violations (1,997 complaints) of any state institution, while the Refugee Commission ranked 10th (333 complaints). Mexican authorities detained at least 281,149 people in overcrowded immigration detention centres and deported at least 98,299 people, mostly from Central America, including thousands of unaccompanied children. During the year, authorities detained several refugees and migrants in airports around the country and subjected them to inhuman and degrading treatment. The country’s refugee agency received 118,478 asylum applications. The largest number of applications came from nationals of Honduras, followed by Cuba, Haiti and Venezuela. Authorities continued to collaborate with the USA in implementing US policies that undermine the right to asylum and the principle of non-refoulement. These included summarily expelling people from Central America and Venezuela under Title 42 of the US Code, which drastically limits access to asylum procedures at the US-Mexico border. People expelled to Mexico from the USA were subjected to multiple forms of violence, including kidnappings, sexual violence and robbery. The Supreme Court issued two landmark rulings for the protection of migrants. In May, it declared that the immigration checkpoints inside Mexico are unconstitutional on the ground that they are discriminatory. In October it recognized that the Executive branch had failed to publish clear official protocols for the protection of people returned to Mexican territory under the US “Remain in Mexico” protocol (also known as the Migrant Protection Protocols, MPP).

Congress again failed to pass a law to regulate Indigenous peoples’ right to free, prior and informed consent on projects affecting them, guaranteed under ILO Convention 169, despite a 2020 Supreme Court ruling calling on it to do so.

Learn more

9 September

Mexico: Militarization of public security will lead to more human rights violations and perpetuate impunity

29 November

Americas: Attempts to militarize public security in the region are a threat to human rights

13 December

Mexico: Rights of feminicide victims at risk

28 September

Mexico: State must guarantee truth, justice, and remembrance for families of Ayotzinapa students

7 October

Americas: Military monitoring of civil society organizations shows deteriorating respect for human rights