By Scott Edwards, Senior Adviser for Amnesty International’s Crisis Response

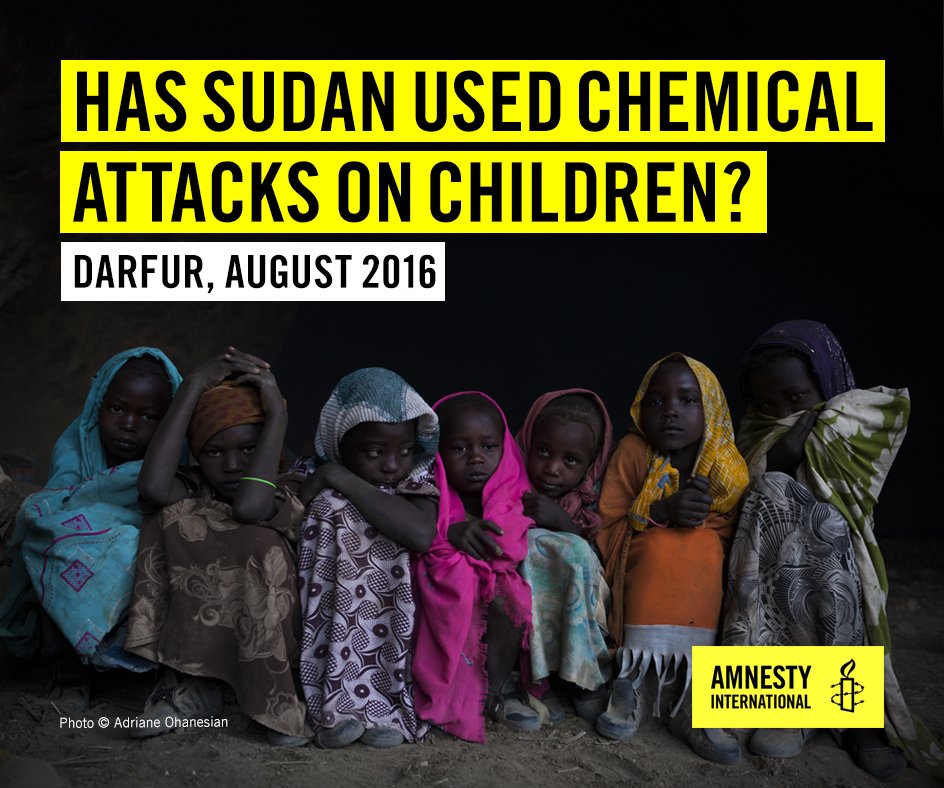

Today, Amnesty International is releasing an expansive report on violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law in Jebel Mara, Darfur, committed this year by Sudanese government forces and allied militia. One of the most troubling findings in this report is the use of chemical weapons, and it is almost certainly the finding that will capture the most media headlines. In many ways, this is desirable: the use of these weapons is an affront to humanity itself and its aspiration to limit the cruelty and devastation of warfare. Their use should capture headlines, as they have most recently in Syria.

But the use of chemical weapons documented in this report—while per se a criminal act—is part of an ongoing criminal enterprise: counter-insurgency waged in violation of the most basic laws of war. Relying on hundreds of interviews, photographic materials, and extensive satellite imagery analysis, the report documents attacks that either damaged or wholly destroyed over 170 villages. In at least 170 villages in Jebel Mara, civilians, their homes, and their livelihoods were attacked or destroyed in systematized fashion. The report also documents widespread rape of women and girls; the widespread killing of fleeing civilians.

The use of chemical weapons must not be evaluated by the international community, competent courts, or by history, in isolation from the other crimes documented in this report.

For over a decade I have worked on Darfur and over that time, the nature of the government’s strategy has continued largely unchanged. Military tacticians usually favor a “drain the pond” description of the strategy, wherein populations are eliminated—whether through direct attacks or forced displacement/relocation—so they cannot serve as bases of support or shields for armed opposition. Amnesty International more aptly describes the strategy as a series of Crimes Against Humanity.

A Criminal Pattern

Notably, Amnesty International’s report is nearly a whopping 100 pages long. We could have readily presented the use of chemical weapons—a war crime—as a less lengthy stand-alone report. But to do so would be to risk missing the forest for the trees. Taken alone, the use of these weapons constitutes a crime; but taken together with the evidence of widespread and systematic attacks on civilian populations in the report, the findings and implications are much more troubling.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for Omar al-Bashir and others suspected of war crimes, Crimes Against Humanity, and—ultimately—Genocide in Darfur in 2007, 2009, and 2010. These warrants were issued based on crimes and patterns of warfare similar to—if not identical—those documented in this report. For those who have followed Darfur over the years, we should find one passage in the report as troubling as any other, and it begins with: “The vast majority of the attacks followed a pattern.” This passage describes attack patterns and grave abuses that could have been taken from reporting on Darfur any time before or since the ICC indictments.

The use of chemical weapons—while a new and egregious crime—is the natural consequence of the impunity enjoyed by Omar al-Bashir and other fugitives from international justice. Since the indictments, multiple countries have hosted al-Bashir and failed in their obligations to arrest him. While the ultimate responsibility for the Crimes Against Humanity documented in this report is borne by those who devised and implemented it, the international community must bear some responsibility for the lack of accountability that has made these most recent crimes possible.

Now, it must act. (see “Recommendations” of the report).

P.S.—In the meantime, there remains much work to do in assessing the scale and nature of human suffering in Darfur, and much you can do to help. The latest Amnesty Decoders project, launching next week, will call on digital volunteers to help analyze satellite imagery from Darfur and identify whether villages appear to have been attacked, damaged, or destroyed.