"Texans know that the air that we breathe, the water that we drink, the land that we inhabit, they are all a reflection of the majesty and the beauty of our wonderful Creator. We must preserve His image. Like most Texans, I am a proponent of capital punishment because it affirms the high value we place on innocent life. We have a good system of justice in Texas, but it can be better."

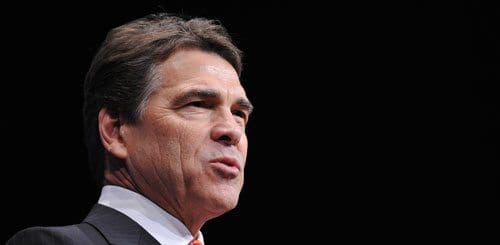

Texas Governor Rick Perry, State of the State address, January 25, 2001

If Governor Rick Perry really meant to put the death penalty on a par with the life-giving necessities of air and water in his 2001 State of the State address, and to place his support for executions directly alongside his religious beliefs, perhaps it helps to explain why the State of Texas remains in a world of its own when it comes to judicial killing. In under a dozen years, Texas has killed more than twice as many people in its lethal injection chamber as any other state in the USA has put to death in the three and a half decades since the US Supreme Court allowed executions to resume under new capital laws. Texas is now set to carry out its 250th execution under Governor Perry. The next two most active death chambers – in Virginia and Oklahoma, combined – have seen 209 executions in the past 35 years. More people have been executed in Texas who were convicted in one of its jurisdictions, Harris County, than have been executed in either one of these two other states.

Geographic disparity on a grand scale – tilted heavily towards the southern states – is just one hallmark of the USA’s death penalty. Others include discrimination and error, along with the inescapable cruelty and incompatibility with human dignity that defines this punishment wherever and whenever it occurs. In 2008, after more than 30 years on the US Supreme Court, its then most senior Justice described the death penalty as “patently excessive and cruel” and executions as the “pointless and needless extinction of life”. Until a majority of the Justices reach such a conclusion, however, we look for principled human rights leadership from elected officials. In the Texas governor’s office, such leadership has been sadly lacking and the quality of mercy emanating from there and from the Governor’s appointees on the state Board of Pardons and Paroles (BPP) remains particularly strained.

On the eve of the second execution to have taken place on his watch, Governor Perry stated his belief that “capital punishment affirms the high value we place on innocent life because it tells those who would prey on our citizens that you will pay the ultimate price for their [sic] unthinkable acts of violence”. Even if one were to accept the notion that taking a prisoner from his or her cell, strapping them down and killing them, can somehow promote respect for life rather than erode it, the state’s “high value” label apparently attaches only to the lives of a few murder victims. There have been around 15,000 murders in Texas since 2001, and 249 executions. While that is 249 executions too many, it is clearly a highly selective approach to retributive killing. This begs the question of how the state chooses who to kill.

The US Supreme Court has said that the death penalty must be limited to “those offenders who commit a narrow category of the most serious crimes and whose extreme culpability makes them the most deserving of execution.” While international human rights standards expect governments to narrow the scope of the death penalty, with a view to its abolition, it is also the case that a majority of countries have stopped executing anyone, whether or not the state considers it possible to determine who the “worst of the worst” are. Moreover, the international community has agreed that the death penalty should not be an option even for those convicted in the International Criminal Court and other international tribunals of crimes such as genocide, torture, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

If the USA’s claim that it reliably limits its death penalty to the “worst of the worst” conjures images of rational, calculating, remorseless killers going to their execution under a capital justice system that weeds out errors and inequities, this picture tends to dissolve when one takes a look at who ends up in the country’s death chambers and how they got there.