The Chinese government stifles criticism of its policies and actions and discussion of topics considered sensitive through increasingly pervasive online censorship. Government critics, human rights defenders, pro-democracy activists and religious leaders and practitioners are among those subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention. Ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Tibet experience systematic repression. The authorities attempted to prevent the publication of an UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights’ report in 2022 documenting potential crimes against humanity and other international crimes in Xinjiang. Women endure sexual violence and harassment and other violations of their rights. The Hong Kong government crackdowns against the pro-democracy movement.

KEY ISSUES

Online censorship grew more pervasive and sophisticated as a tool to stifle criticism of the government, intensifying around high-profile events and anniversaries. All discussion and commemoration of the victims of the suppression of the 1989 pro-democracy protests remained banned.

Authorities intensified their efforts to prevent criticism of Covid-19 lockdown measures on social media, including appeals for help by those under lockdown and allegations of human rights violations in quarantine facilities. Authorities manipulated the Covid-19 health status phone app that was required to enter public buildings and shops and use public transport or travel, to unduly restrict freedom of movement and peaceful assembly.

Large numbers of people were detained for participating in peaceful protests against Covid-19 restrictions following the fatal apartment fire in Urumqi in November. It was unclear how many remained in detention at the end of the year. Videos circulated online showed police beating protesters during arrests.

Authorities continued to imprison human rights defenders, including citizen journalists and human rights lawyers. Those detained were held in harsh conditions and subjected to torture and other ill-treatment.

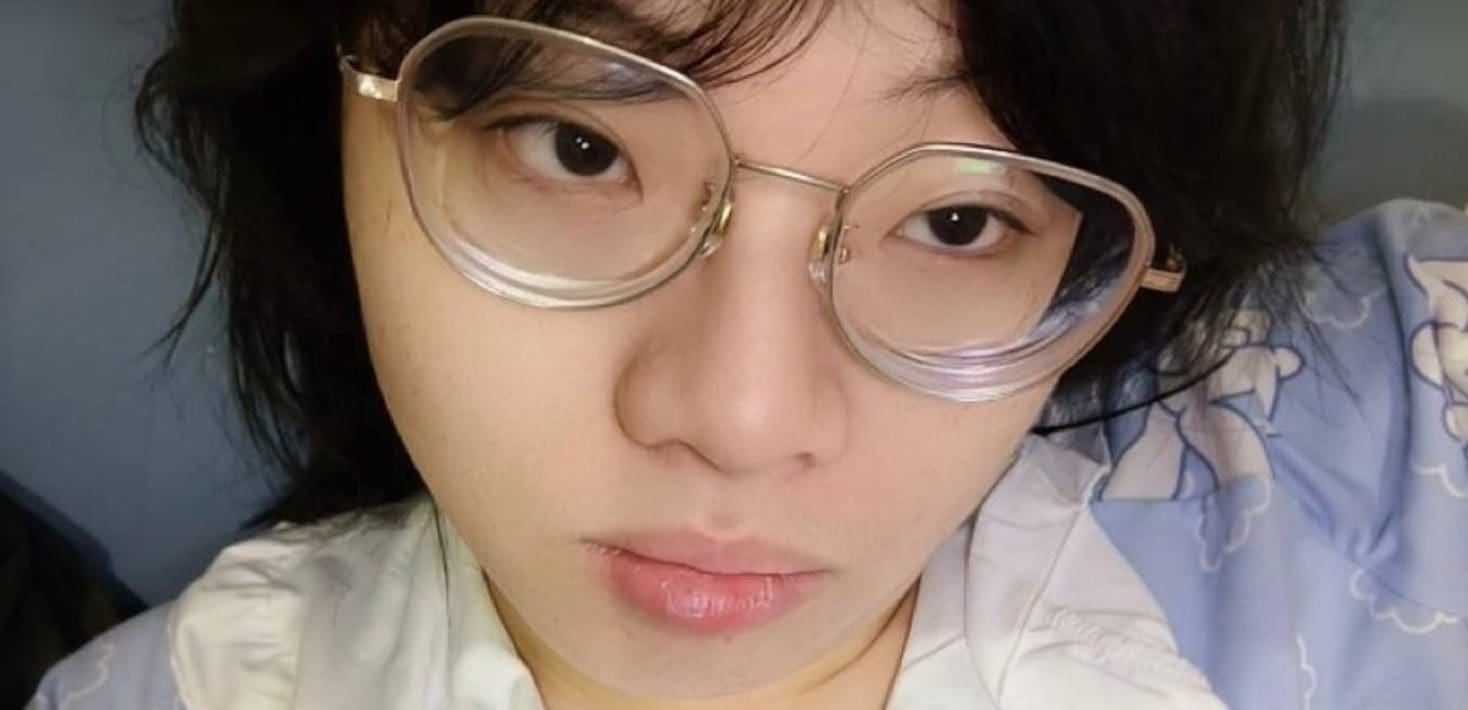

In January 2022, citizen journalist Zhang Zhan, who was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in 2020 for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” after reporting on the Covid-19 outbreak, ended her hunger strike to stop the authorities from further force-feeding. It was unclear if Zhang Zhan, whose health had deteriorated during her hunger strike, was permitted access to appropriate medical care.

In April 2022, there were reports of serious deterioration in the health of Huang Qi, the imprisoned founder and director of the Sichuan-based human rights website “64 Tianwang”. Huang Qi, who was serving a 12-year prison sentence for his human rights reporting, reportedly did not have access to adequate medical care and was denied access to a bank account where friends and family had deposited money for him to purchase medical and other supplies. He had been refused all contact with his family since 2020.

Many lawyers remained in prison or under strict surveillance. They included legal scholar Xu Zhiyong and human rights lawyer Ding Jiaxi, who were tried in secret in June 2022 after being indicted for “subversion of state power” in October 2021. The two men were prominent members of the New Citizens’ Movement, a network of activists set up to promote government transparency and expose corruption. Neither had access to lawyers in the months prior to their trials.

In April 2022, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called on the Chinese authorities to immediately release labour activist Wang Jianbing. He was detained in Guangzhou in September 2021, along with #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin, and charged with “inciting subversion of state power” in connection with their participation in private gatherings in Wang Jianbing’s house to discuss shrinking civil society space. Both were held in incommunicado detention and subjected to ill-treatment following their arrest.

Harassment and imprisonment of individuals for practising their religion or beliefs continued. Religious leaders and practitioners, including those belonging to house churches, Uyghur imams, Tibetan Buddhist monks and Falun Gong members, were among those subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention during 2022.

China remained the world’s leading executioner, although the government continued to classify statistics for executions and death sentences as “state secrets”. The death penalty remained applicable for 46 offenses, including non-lethal offenses that do not meet the threshold of the “most serious crimes” under international law and standards.

Ethnic Tibetans continued to face discrimination and restrictions on their rights to freedom of religion and belief, expression, association and peaceful assembly. Protests against Chinese government repression nevertheless continued.

In September 2022, the Kardze Intermediate People’s Court in Sichuan sentenced six Tibetan writers and activists to prison terms of between four and 14 years for “inciting separatism” and “endangering state security”. Gangkye Drupa Kyab, Seynam, Gangbu Yudrum, Tsering Dolma and Samdup were detained in March or April 2021. Pema Rinchen was detained in late 2020 and held incommunicado until his trial. All six had been arbitrarily detained in the past in connection with their writings or protests against the Chinese authorities and several suffered from health complications as a result of beatings, poor detention conditions and other ill-treatment experienced at the time.

Tibetan monk Rinchen Tsultrim continued to be denied any contact with his family and access to lawyers despite repeated requests by his family to visit him since his detention in August 2019. He was sentenced to four-and-a-half years’ imprisonment in November 2020 following an unfair trial.

For more information on Amnesty International’s work on China, refer to the links on Xinjiang and Hong Kong in the introduction above, the links to news releases / actions below, or contact the AIUSA China Coordination Group.

Relevant Links

- Urgent Action: Activists Approaching One Year in Detention (Yu Wensheng and Xu Yan)

- China: Tibetan monk jailed for Wechat posts released (Rinchen Tsultrim)

- ‘I yearn to see you’ – Valentine’s letters to activists detained in mainland China and Hong Kong

- China: Activist Li Qiaochu unjustly convicted ‘for speaking out about torture’

- China attempts to ‘gaslight’ international community at UN human rights review

- China: Trial of activist Li Qiaochu is thinly veiled attempt to silence rights activism

- China: After six years deprived of liberty, human rights lawyer finally sentenced

- China: Human rights lawyer at risk of torture after return from Laos

- China: #MeToo and labour activists facing ‘baseless’ trial must be released

- China: Anniversary of UN’s damning Xinjiang report must be ‘wake-up call’ to action

- People’s Republic of China: Human rights situation at new low: Amnesty International: Submission to the 45th session of the UPR Working Group, January-February 2024

- China: Jail sentence for lawyer who reported being tortured ‘an outrage’

- Take Action: Protect the memory of the Tiananmen Square crackdown

- The hidden history of China’s protest movement

- China: Heavy prison sentences for human rights activists ‘disgraceful’

- China: European states must investigate potential involvement in crimes against humanity by visiting Xinjiang governor

- China: Submission to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: 73rd Session, 13 February – 3 March 2023

- China: Government must not detain peaceful protesters as unprecedented demonstrations break out across the country

- China: Xi Jinping’s continued tenure as leader a disaster for human rights

- AI Report: China 2022

- What China says, what China means, and what this means for Human Rights

- Press Release: Draconian Repression of Muslims in Xinjiang, China Amounts to Crimes Against Humanity